Sian Kennedy. Aslan Remembered

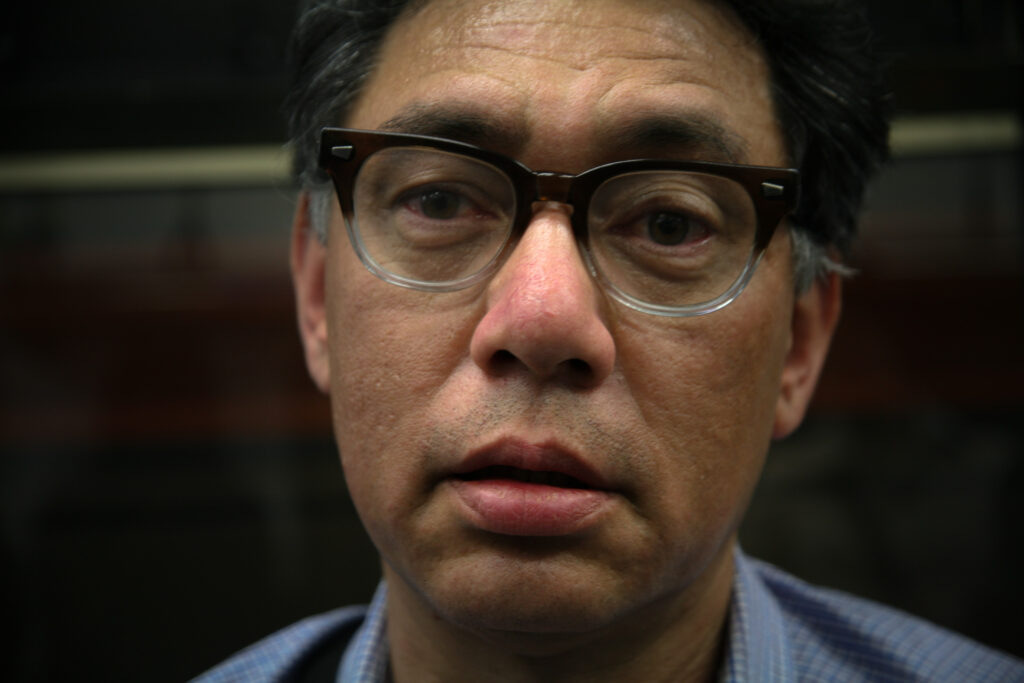

I met Sian some time in the mid-90’s. I’d flown out to LA, ostensibly to show my face at a shoot and was sleeping on a sofa afforded me by Micheal in a gaudy Hollywood suite afforded him by some forgettable, forgotten client. Sian bowled up early to do the stuff assistants do; the dull litany of testing equipment, calling things names, plugging ‘em in, making ‘em pop. A little older than average, he was large, quiet and inscrutable. Assistants back then conformed to a familiar taxonomy – affable bro-dudes who knew everything about f-stops and the Violent Femmes and not much about anything else – and while Sian was content to cover the bases, he was clearly functioning on a higher plane. Steadfast but not servile, he took it all in whilst plugging and unplugging, with a neutral tone and single cocked eyebrow, checking out the syntax of this latest pantomime; nice-guy photographer and his verminous agent who seemingly wanted to be involved whilst claiming to want as little involvement as possible, and who wouldn’t (or couldn’t) shut up or shell out for a room of his own. Sian had the steady gait of a human whose abilities were leagues beyond what was being asked of him, but who‘d see things through with minimum fuss nonetheless. He was half-Chinese (no, it’s important, Sian can’t be Sian without that observation) and really big. A big man, with big features, big limbs, big lips, a slow smile and steady gaze; he seemed like he was actually processing stuff before speaking, unlike this scattershot weasel agent dude he was being forced to endure. I didn’t end up going to the shoot. Of course. I ran off with Chris Buck to do something that suited my performative ego better. But the connection had been made, and a few weeks later Sian flew to New York and we sat down together in my fleabag office on Broadway with a book of his pictures.

Nobody got what he was doing back then. Certainly not me. I’ve been given credit for prescience, but in truth I was clueless.The pictures were all of LA, high-tone, blown out. Hints of Martin Parr and Gary Winogrand, but not enough for me to nod sagely and rubber-stamp as derivative. Nothing was straight or well-made. Which is not to say it was badly-made. It was as if he’d gone through well-made and was passing weird-made on the road to not-made-at-all. Maybe in search of the un-photo or something. Imagine somebody shuffling through their Auntie’s holiday snaps and being blown away by something he found; the innocent vulnerability, an ache towards magnitude, the soft bulb of hope, squashed. And then setting out on a journey towards that, to crystallize it, and not just by accident but by endeavour.

‘Isolate rather this element

That spreads through other lives like a tree

And sways them on in a kind of sense’

Also nobody could get his name right. It was a constant process of repeating it and explaining that no, he wasn’t a girl. So I crossed the ‘i’ and he became Stan, which lengthened to Stanley, which solved all problems at a stroke. The Stanley I was picturing was the one from Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party – holed up in a boarding house with chattering Meg and silent Petey, waiting for Goldberg and McCann to come and snap his horn-rimmed spectacles. To this day, the conspiracy of thumbs and autocorrect refuses to succumb to reality. Along with Stan I get Asian, Aslan, Stun and Siam, all oddly appropriate in their own sweet ways.

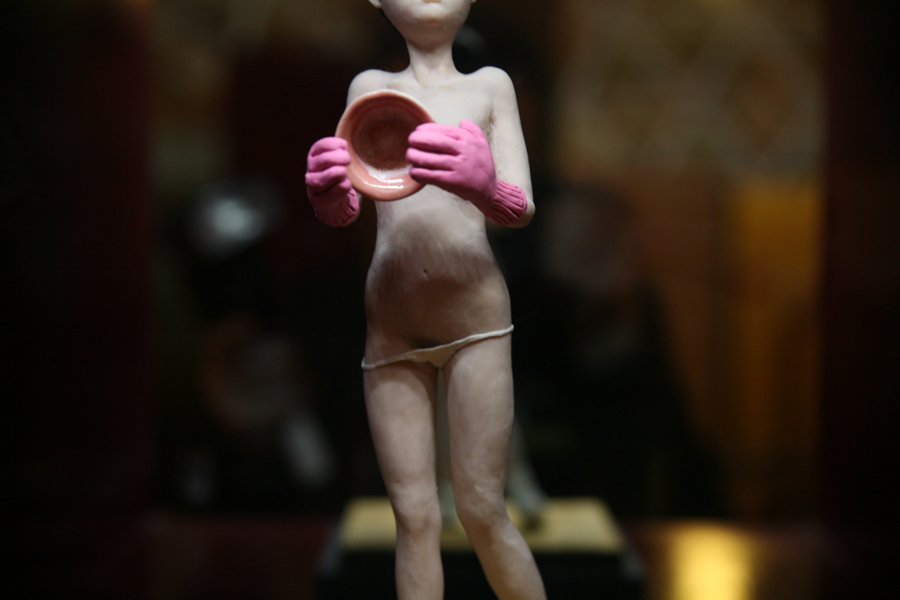

Stanley had a radar for what he called ‘the endearing side of pathetic’. He found it everywhere; crudely-pruned topiary, a badly fitted air-conditioner, the way two cats’ tails coalesced, a baby’s hand in spaghetti. Later, when we traveled together, he’d stop at the perimeter of some parking lot, see a misspelled sign in the back of an RV, get up close on a collection of miniature football helmets roasting in the window of a car. And he’d just kind of stare, shake his head, say “fuck,” then burst into gappy-toothed laughter. Like he’d seen the tragedy of humanity in a can of Febreze on a motel toilet. Fear in a handful of dust. And it wasn’t condescension; it was solidarity. Stanley, like the people and stuff he encountered, was struggling to make it through in the face of toppling absurdity. What stopped him in his tracks were the myriad, manifold gestures humans make to survive being human. The hopeful, hopeless squeaks. If it sounds contrived, it wasn’t. Abjuring an orthodoxy that purports to ennoble the human experience with pseudo-art and soft furnishings is not cynicism. Quite the opposite. Nothing about Stanley was contrived. He might have been the least contrived person I’ve known.

I took him on. But not because of the pictures. I did it because I knew we were going to be brothers; that the journey ahead would be brilliant. I think we both had a sixth sense for such things. Simon, my own brother, at my shoulder whispering “yes!”

We baptized our new friendship with travel. It’s always best. Travel brooks no separation, demands you to take your stupid bags off the seat, feel somebody’s buttock against yours, the pluck and knock of their humanity. We went to Ecuador, kicked around Quito, then rented a car and set off east along the road that bridles Amazonia; Tena, Puyo, Coca. Neither of us had been before; we had no itinerary, nowhere to stay, no ideas other than being present for each other and whatever we encountered. An unspoken credo; no moods, no demands, no sulks or drivel, no claiming there were better ways to do things, find, cook, eat or be in thrall of things. We had plastic cameras and shot everything we passed, avalanches of pictures, never for their own sake, but as divining rods for where the juice was. Stanley taught me that photography was a reason to get out of bed at dawn and still be up at two. It didn’t matter if the pictures were crap. Nearly all pictures are crap. It’s a crap medium. Avoiding crappiness was to miss out on the easy immediacy it afforded, an expressway to intimacy. And even if you tossed it all away when you got home (we never did), at least birthing it put you at the nexus where the shit meets the shit, and almost always before anybody else turned up. A privilege and an incantation.

In Misahualli we met the daughter of Douglas Clarke, pioneer of Ecuadorian river travel. Stanley made friends quickly on the road. It’s funny, in private he was exacting in his habits, a trait which sometimes sublimated into solitude. But out in the world he was able to channel his size, the amount of sheer corporeality he commanded, to foster a grinning, windmilling presence that people found instantly engaging. He taught me that what people want is to see and be seen, that epiphanies spring from making yourself available. Be there. Don’t turn away. Grin like an idiot and gleam. Douglas’s daughter took to him straight away, radiant in the oversize Pantera t-shirt he’d bought at a market in Quito, and half an hour later we were in dugout canoes heading east down the Rio Napo. The camp we arrived at adjoined an indigenous jungle village; school, medical clinic, shed by the soccer pitch with potato chips, plantains and coca-cola in plastic bags. We had a hut, one of maybe five or six, but nobody else was around and nothing was happening. That night we took the canoe out onto the river, found an eddy, turned off the engine and sat in darkness and silence as the jungle forgot all about us and returned to its astonishing, obscene cacophony. Just me and Stanley, holding our breath, experiencing the carnal ecstasy of not existing.

The next day they asked if we wanted to come downriver to see a women’s cooperative weaving workshop and sample some chicha and we said no. The village girl’s soccer team was playing another village’s girl’s soccer team and we’d stick around for that. In a scrappy jungle clearing with grass like needles, it turned out our team were short of two players; so we were drafted in. Stanley, twice the size of everybody, was goalie. He was no sporty guy. He was a big lummox. But because he was so big (and the girls so small and bad at soccer) he could save every goal. He’d just kind of reach out and pick up the ball, like that was what he haplessly believed he was supposed to do. The girls howled with indignation. They’d never seen anything like it. And he’d stand there, beaming like a clown, holding the ball out as if it was something wonderful he’d found in the bushes. The game descended into chaos. One girl would dribble up slowly while the rest piled onto Stanley, allowing their teammate to walk the ball into the net. I’ve never seen him happier. As happy, but never happier. It’s was breathless, all of us on our backs like beetles crying with laughter in the sea-urchin grass, fighting for air. The transcendent love some primal deity came up with to suggest there might just be a point. So far from home, so deep in the jungle, complete strangers, no common language, no common anything, the apogee of what it is to be a human amongst humans. When we got back to the States we had chiggers, mine to my knees, Stanley’s of course (everything he caught went bananas) all the way up the smooth, mighty trunks of his legs to his thighs, waist, and everything between.

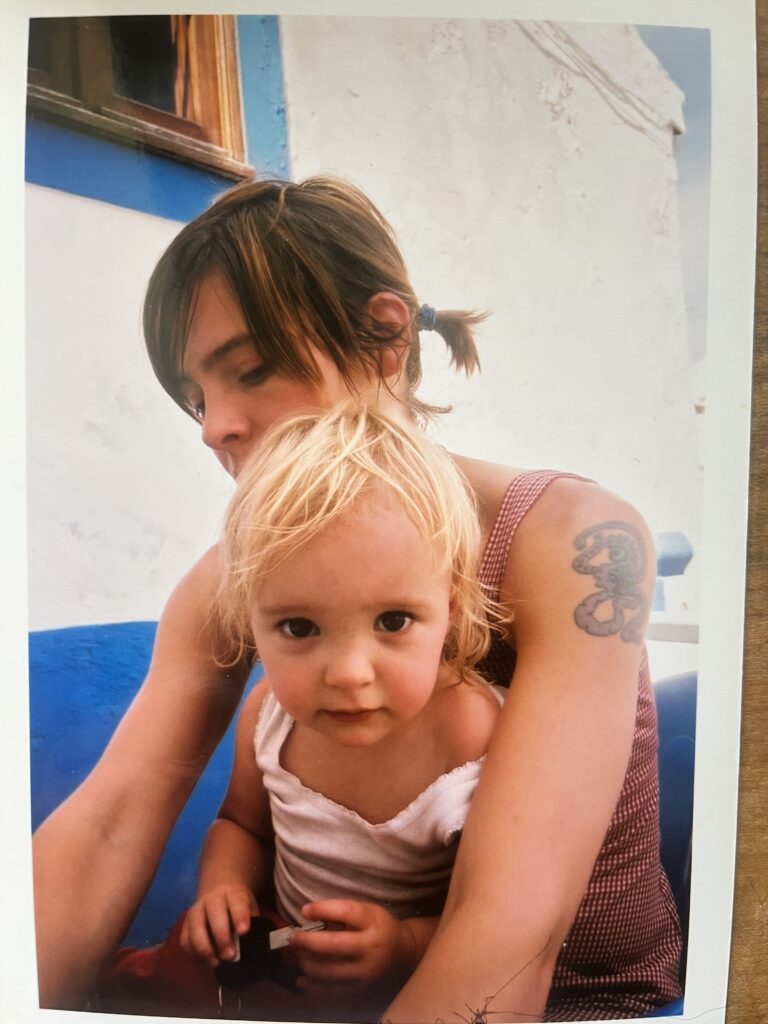

A few months later he was in New York and Juliette and I had just had Winnie. Things were crazy, we were ragged, full of ideas about raising a baby at the same time as not having a clue. He swung by the apartment on Rivington, and Juliette quickly fell in love, just as I had. Thereafter, even if it was usually Stan and me on the road, we were a trio in spirit.

We arrived in Cartagena at the height of the FARC kidnappings, the only foreigners in a town that wasn’t expecting us. Whatever tourist infrastructure had once existed was now invisible, rendered worthless by the threat of not making it home without a ransom. We stayed a night or two, rented a car from a guy’s brother and drove out past Barranquilla. By the time we reached Santa Marta we’d been stopped three times and shaken down for cash. If we kept going we’d be broke. So we drove back and flew to Riohacha. Stanley had an idea about a place on the very tip of the Guajira Peninsula, a place of absolute nothingness where desert meets sea in a seamless state change, solid to liquid. No hills, no trees, not a wrinkle to muddy the encounter. Stanley meets Livingstone on a faint pencil line, absence on absence. He was determined to see it. The roads out there shifted with the motions of the desert, unmapped, traversed only by barreling oil trucks. It would be like The Wages of Fear he said, a film he cherished. Kicking around empty Riohacha for three days trying to convince a driver to take us out onto the sand, Stanley introduced me to the concept – which I have clumsily adhered to since – that the practice of traveling was to gravitate towards nothing. Because any idiot can find something. There are signposts everywhere piled up like pizza boxes in a dumpster. The rues of Paris, the campos of Venice, all swarming with human seagulls. Somewhere’s a no-brainer. Just like how anybody can take a well-made picture. Childsplay. Learn the syntax, press the button. There’s no mystery in something, just a ceaseless swabbing to keep metaphysics from seeping around the seams of your underpants. Stanley’s fascination with nothing echoed his pursuit of the un-picture, the architecture of which, when found, would be so blank your eyes would slip off the emulsion and puddle onto the linoleum. Inhabiting nothing was a higher calling, a state of grace. We got to the north of the peninsula in a pickup, stayed two nights in hammocks until our driver returned and plucked us from hunger and boredom. I remember nothing except walking along the sea-line and collapsing into shared fits of laughter at our ridiculousness. Oh and not sleeping, being bitten bloodless and wading out into the sea, which never got deeper than our thighs no matter how far we went. We could only wave. Drowning would have taken real commitment. And there was nothing, not even a Waiting for Godot tree to hang memory on. We were Vladimir and Estragon wandering through some sun-soaked James Turrell installation in which time and sense are terminally suspended.

Our driver took us to Maicao, a pirate town on the border of Venezuela. It was full of Arabs and Stanley was immediately purring. His childhood, like mine, had been one of constant motion. His father, a professor of cultural anthropology, had moved the family all over the world; Cairo, Nubia, Mexico, Chico, Buffalo. But Stanley’s particular ache was for Sanaa, Yemen, and memories of men on upper floors of concrete buildings talking and chewing Qat. Maicao had undertones of that; a huge mosque surrounded by a garbage heap of buildings, the febrile boredom of trading, goats bound at the feet for slaughter and – for the first time in Colombia – the snaggle-toothed murk of danger. Our driver filled the truck by signaling to a kid at the side of the road who put his mouth to a rubber hose and siphoned gas from a clutter of rusty cans. Then he left us. That evening as we we were walking beside a desolate modern building in the centre of town – perhaps once a hotel or television station – an SUV with tinted windows pulled up on the sidewalk and men jumped out of all the doors. Stanley mumbled something like “oh dear.” It was one of the few times in my life I felt I might unknowingly have stepped across an invisible line and be in real trouble. Nothing happened. We turned and walked in the opposite direction.

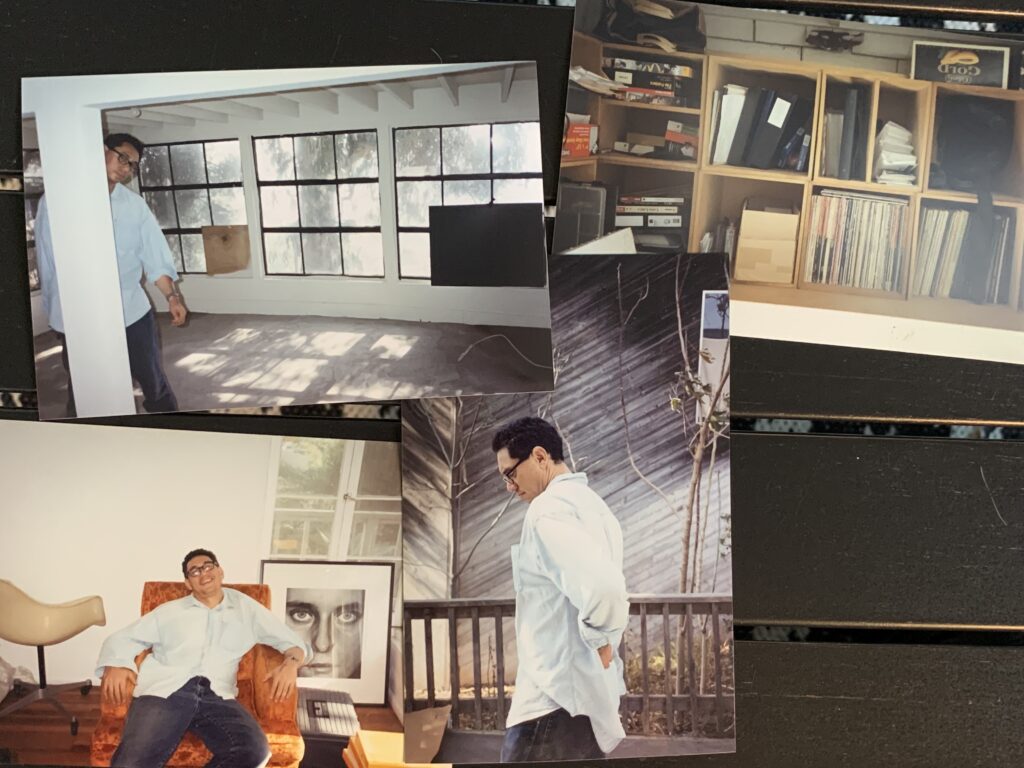

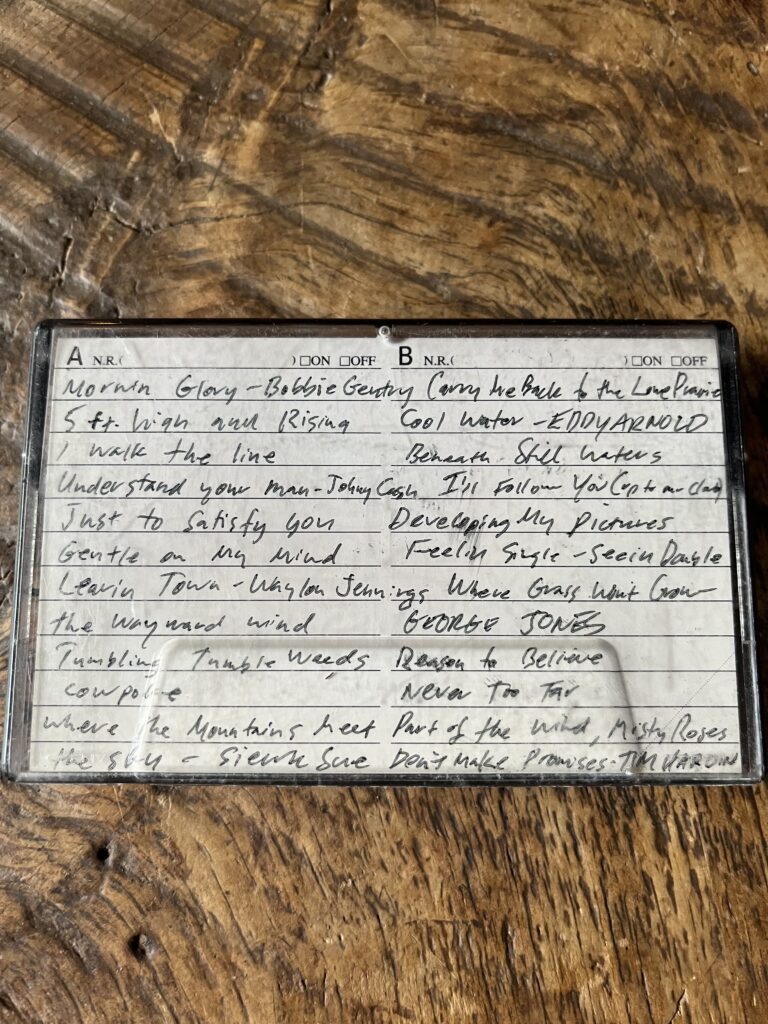

Stanley’s Kilbourn house was a revelation. I can’t remember how he came to be in it; having been savaged by his maniac neighbour’s maniac dog at the place on Ripple, he somehow cobbled enough cash together to buy this flyblown shack clinging to the face of Mount Washington. It was a masterpiece of hobo construction, knitted together by the Lorax out of truffula branches and Thneed yarn. You felt that if you moved around too boisterously, the whole enterprise might uproot from the mesh of rhizomes tethering it to the hill and plunge headlong into the LA River. To me it was a sanctuary, a sofa with a single sheet in Paradise, exotic and a little bit Hollywood cartoonish, kind of like The Flintstones. It came with a parallel life, profoundly different from (but as rich as) the one I had back east. I’d fly into LAX, rent a car and chariot north, windows down, that amazing warm, fragrant air and lilac sky, to the goofy box on the hill where Stanley would be waiting, beaming, with a cocktail and one of those vast hugs, like being subsumed by a human futon. We’d do our first tender waltz over monumental gin and tonics, fluttering our eyelashes and blushing, a crush reborn, before scooting down the hill for cheap tacos (my demand) and back up again to spend the rest of the night chattering like crickets, sucking down bourbon, playing records. Anybody who listened to music with Stanley will confirm how fervently he occupied it, chewing it, writhing in it, wrestling it to the ground. Always on vinyl, between thunderclaps of laughter, his fingers curling and uncurling, kneading the air like he was invoking the souls that incanted it. Walt Dickerson, Thelonius Monk, Robert Wyatt, John Cale, George Jones, Tim Hardin, Mama Cass, Snoop Dogg, Waylon Jennings. As the lights of Dodger Stadium below clicked on, endured, and clicked off again.

We’d stick around for a couple of days before heading out on the road. Stan would have a few last chores to do, and I always needed a dose of LA, like swigging from the Robitussin bottle. During the day we’d do life stuff; running equipment to Samy’s, chiropractor appointments, the corollary of Stanley being broadsided by a wasted driver who jumped a red light in Compton. Or we’d go see his mum, Sylvia, in Manhattan Beach, a wry, funny lady, and she’d cook us Chinese food. Running around LA with him felt like being a passenger in Elliot Gould’s car in The Long Goodbye; lots of oddball characters in out-of-the-way places who knew Stanley, had known him for years. Evenings he’d run me around his haunts in East LA, watch the mariachi bands congregate in Boyle Heights; or go downtown, get french dip at Philippe, something sloppy at Clifton’s, maybe even dinner at Musso and Frank. All cheeseball tourist stuff probably, but it was magical old LA for me, and Stanley loved the place, was thrilled by how intoxicating I found it. He was happy there in the white light, white heat, constantly amazed by the weird shit it regurgitated, its relentless horizontality – the world through a letterbox – untroubled by the tyranny of the perpendicular. LA was in the fibres of Stanley’s ligaments. It’s hard to imagine him living anywhere else. He was the preeminent visual documentarian of the city from the late 80’s into the oughts. One day everybody’s going to want to remember how it all felt, and Stanley Kennedy’s stuff will be the reservoir they’ll be needing to tap. I only hope it’s still there when they come looking.

These were the days before Stan bought the camper-van, that intemperate guzzler of resources, so after a few days in LA it’d be the two of us in the rental car heading out into the desert through Nipton, or south to Tijuana, kicking along the frazzled fringes of the Salton Sea and back up the other side to Salvation Mountain and Slab City. Or east to Vegas through Barstow, flyblown meth towns with bowling alleys and garage sales and curtains flapping out of windows. We’d stay wherever we found, eat whatever we were given. There was the time I flew out during the prolonged nadir of James Smolka’s illness; we were on call to Constance for word of the end – me, Juliette, Stanley, Micheal, Dennis – and it was too intense, all of us too callow to process the gothic contortions of a young friend enduring the death of an old person. Stanley and I were holed up in a motel in Calexico, I couldn’t sleep, so I got up and was wandering the town at dawn when the call came in. Only it wasn’t James. It was another friend, still younger, who had gone. Without a note of warning she had thrown herself into traffic on a dual-carriageway near Nottingham. I went back and Stanley was up. We walked out into the furnace heat and got coffee. It was like we knew all along that the gun wasn’t empty; there was a bullet in it. Only it turned out there were two.

I was close with several of the photographers back then, traveled extensively with a few. Chris, David, Henrik, James. The difference with Stanley was that he was family. Juliette loved him. That classification rendered him unique in the pantheon. In general friendship with photographers was dogged by the migraine of photography; time spent living was haunted by the spectre of work lurking in the shadows like a sweaty Mormon. Shooting it, looking at it, shuffling and reshuffling it, bemoaning not having enough of it, how to get more of it. Specious stuff, and photographers often don’t understand how little the rest of the world cares. Juliette specifically. But we didn’t do that with Stanley. Stan was all soul, any whiff of the soulless made him miserable. We did other things. We rented an enormous RV at the height of summer and went to Needles. Monument Valley. Bryce Canyon, Canyonlands, the Grand Canyon, any damn canyon we could find, Winnie rattling around in the back like a glazed pork roast. We went to Vegas, camped in the car park at Circus Circus. He’d come stay with us upstate and on the Lower East Side, he and Juliette would get deep-tissue massages from some New Age nut-job Stanley had sat next to on a plane. What kind of masseur massages asses and boobs? We lived in his friend’s house in Mertola, Portugal, drove down to the seaside. And the narrative was full of wit and soul, always what actually mattered, never what patently didn’t. Laughing about how weird, fucked up and wonderful the whole shitfest is. But it wasn’t dark. People have told me they considered Stanley to be dark, or at least a person conversant with darkness. Perhaps because he didn’t giddily adhere to the orthodoxy of aspirational ninnyism, the vanilla imperative always to be nice. Of course there was darkness, it’s a function of intelligent discourse. It’s only always light in the shallows, and we weren’t going to sit around exchanging frittata recipes. It was communion, uncensored, without fear of offence, given or received. How decent, normal friendship should be. And rare as hen’s teeth.

Sometimes I’d join Stanley on jobs if they were juicy or far away. We met up in Seoul to do a story about food. So odd. I mean, Stanley, food? But people were always wanting pictures of it so I said, “oh yeah, he does food.” Food’s the bottom of the food chain, ninny clusters of inanimate matter sniveling on a plate, culture distilled to inanity. And in reality Stanley did shoot food; food that fought back. A foot-long frankfurter gripped at the waist by a bloody four-inch bun sweating in a plastic case on an empty car ferry off Gdansk. Food that spoke of the humans who consumed it, waving, drowning. But nobody wanted that, and since Stan was a professional we used sleight-of-hand to snag some of the drivel. In Seoul, after covering the obligatory colorful market, its cheerful traders and their calloused hands, we ate bloody BBQ, watched drunk businessmen pass out in the street and got massages from middle-aged ladies in offices that felt like surgeries. Stanley loved massages. He was always hurting from some calamity or other, and his body was a vast, soft landscape for trained thumbs to exercise purchase on.

In Busan we ate raw fish still twitching from the blade on plastic tablecloths served by men in yellow sou’westers wielding garden hoses. We also went to the world’s largest bathhouse. Ushered in by Korean grandfathers, issued loofahs but nothing else, we were suddenly stark naked next to each other in the sultry air, determinedly maintaining eye-contact. Despite frequently sleeping inches from each other, Stanley and I were content to let our own genitals be our own business. Not for us the ‘look at my knob!’ bromance of the Maine dude-sauna, nor the performative upstate pond-swimming sausagefest. So this was virgin territory. We shuffled in and parted, me to an area that looked like an abattoir sprung with spigots at which men, contorted like pretzels, went at their perineums with scrubbers as if grating fridge-hardened cobbles of parmigiano. Why anybody’s asshole would require such a holocaust was unclear, but mine was puckered into an asterisk and bleating ‘don’t even think about it’ alarms. Stanley had removed himself to the corner of a huge hot bath, where he sat immersed to the nipples like the compassionate Buddha until we both agreed the fiasco was over.

We took the MV Sewol overnight from Busan, the same ferry that would later capsize in the Sea of Japan and send 306 passengers to a watery grave. No such theatrics on our crossing. We were on our way to Loveland, Jeju’s Museum of Sex, an open-air theme park studded with lurid totems celebrating the manifold glories (and a few of the pitfalls) of heterosexual copulation. Every prong, knuckle and whorl of the human anatomy supersized and flapping in the breeze, along with graphic renderings of all the eye-popping things you can do with ‘em. Tenderly cruised by grinning families and shy couples from Gongju. Korean children, it seems, are content to stand diddling a tamagotchi even as Mum and Dad gaze lovingly into a drooling vagina the size of a Volkswagen, energetically pressing buttons to make the crenellations shudder like a jelly trifle. And blast your eyes if it isn’t Telly Savalas’s gleaming dome emerging, wet as an elephant’s eye, from a rubbery hijab at its northernmost apex. Stanley was delighted. Me, probably more so. We spent the whole day there. Somewhere in Stanley’s file storage there are burly hard drives oozing terabytes of dirigible Korean cocks stabbing at zettabyes of multifoliate vajayjays.

We shot boondoggle Indian casinos in Connecticut, multi-million dollar museums larded with waxwork Pequots in canoes, their bare-breasted squaws crushing flint corn with heap-big pestles; the casinos cheap and teeming, the museums empty and forgotten, tumbleweeds blowing through their tallow teepees. And in the high-security reservation, up gated driveways bristling with cameras, Range Rovers, Mercedes. We shot the world’s biggest strip club in Vegas, a week sluicing through the tubes and glands of a 24-hour meatmarket, an Amazon warehouse of Amazons, bronzed, deodorized, depilated, herded in on $20 Southwest flights from LA. And they all loved Stanley. Swathes of silicon and filler festooned around the pool at the Rio, libidinous Slurpees frothed up to quench the unquenchable thirst of America’s fattest and drooliest.

Picking Stanley up in Reykjavik after a week in Greenland, we set off for Raufarhöfn, where the world ends by plopping into the sea with a whimper, serenaded by puffins. Along the way we made friends at the Siglufjörður Herring Museum and detoured to Vopnafjörður where Stanley was eager to locate the teenage home of Linda Pétursdóttir, Miss World 1988, devout collector of wind chimes. By now all the fjörðurs, staðirs and hólmurs had been reduced by weary map-reading to cuddly prefixes: Siggy, Stikki, Eggy, Snuffles. We approached Vop with considerable excitement, almost immediately locating Linda’s bungalow opposite the town mailbox. “Linda’s not here,” said the lady in the Spar. “She moved to Canada. We’re closing now.” We went to the gas station for dinner, got four hot dogs with crunchy onions. “You can stay at Einar Einarsson’s. He has a bedroom,” said the spotty boy gazing out blankly from under fluorescents. In the low afternoon light of a sub-Arctic three in the morning, Stanley and I sat on still swings in the playground of the sleeping town, lone survivors of a nuclear disaster from a Nevil Shute novel, sharing the invisible line between night and day and a bag of Gummi Bears.

Which leads us to the overwhelming question. What horrors can have occurred, what terrible schisms, whereby almost fifteen years later I find out, in a message from a friend, that Stanley has been dead for more than a year without Juliette or I having a clue? How do you go from sharing everything with a person to knowing nothing about them? Not even the birth of their non-existence. Again, nothing. Nothing happened.

You do not come dramatically, with dragons

That rear up with my life between their paws

And dash me butchered down beside the wagons,

The horses panicking; nor as a clause

Clearly set out to warn what can be lost,

What out-of-pocket charges must be borne,

Expenses met; nor as a draughty ghost

That’s seen, some mornings, running down a lawn.

Nothing more than the process of looking away for a moment, which becomes a day, a week, a month. Absorbed and embarrassed by the machinations of our lives, not sure how to parse it all appropriately, we neglect to reach out. By titration, the pool of neglect becomes a year, maybe two. And from having had nothing to say, we suddenly find we have too much. The right time to talk has passed, the plot has thickened. There were the ‘you are on my mind’ and ‘I think about you often’ emails, but somehow they didn’t coalesce into rapprochement. Sian had got married and had a kid, something he’d ached for and worried would never happen. We didn’t know Lori, neither Milo. Work had dried up, he’d moved to Seattle, rented out the Kilbourn house. Resources, time, money, were no longer on our side. And besides, our friendship had always been a tight triangle, we’d never got round to the hard labour of including new people. We might have muddled through, worked out some kind of broader family communion had Juliette and I not then parted ways. The awkwardness of divided loyalty – the perceived need to take sides – exacerbated what had already become a kind of estrangement. Then I closed the agency and found myself allergic to photography and photographers. Not that Stanley was tarred with that brush, but the pall of aversion had broad fallout; everything conspired to aggravate the silence. It became less about anything in particular and more about failure.

It is these sunless afternoons, I find,

Instal you at my elbow like a bore.

The chestnut trees are caked with silence. I’m

Aware the days pass quicker than before,

Smell staler too. And once they fall behind

They look like ruin. You have been here some time.

And after that, time. Innate assumptions … habit for a while … harden into all we’ve got. New friends arrived who served to occupy the spaces Stanley had occupied; not exactly, of course, but (in the fog of a life) close enough. Just as Stanley occupied the spaces of those who came before him, and we did for him. It’s a tidal thing, and none of us can be too hard on ourselves. People wash up in each other’s lives. Blame the motions of the sea, the way the wind blows; and in the end it’s to be celebrated. What a gift. To have had the peculiar and wonderful coconut that is Sian Kennedy for the years we did. Having lost him, would we rather he had not washed up at all, or us not have washed up beside him? Would the panacea for the pain of his loss be to have never known the thrill of having him? Absurd. We stay as long as the sea decides, until some faltering weather-pattern sends a wave or two to pluck us away. For a while we see each other in the water, we could try to swim over (we fully intend to) but each of us has our own stuff going on, we’re just trying to make it through or back to shore. And anyway, he’s a strong swimmer, he’ll be okay, we’ll drink and laugh about this later. And each time you turn he’s a little more distant, and then suddenly he is much further out than you thought. And is he waving?

No. No, he isn’t. And in the scheme of the metaphor, that’s what hurts the most. You cannot help but feel your ministrations could have been of use. That the residual joy contained in the communion you once shared might have constituted enough flickering light to make persisting seem worthwhile. To keep the swimmer swimming. Had you just crossed the rubicon of time and neglect and proffered a hand. But of course this may just be narcissism. We cannot know the dimly-lit rooms inside another person’s head, what pain or emptiness they have encountered, pushed through, encountered again. Or what reiterative boredoms. The idea that our love might have been enough, the straw taken from the camel’s back, may be little more than hubris. Stanley was no dummy. The idea that he had not visited this possibility, indeed each possibility of transcendence, and found it unequal to the burden, is nonsense. Nobody can be expected to persist indefinitely for anybody else’s sake. All we can hope is that they try. I cannot doubt Stanley did that. With every grain of his humanity, for Milo, for Lori.

In the end there is just the bit of ant track we are on, and even that is gone the moment it is acknowledged, no sooner present than it turns to past. The only agency we have is to keep walking or to stop. The rest is this disease of consciousness, the pyrrhic gift of being able to reflect and project. Perhaps even joy (or its opposite) is explicable by some combination of chemistry and instinct; that we’re just a clutter of chemicals glued to a primal imperative to keep going, to make more. More, all of whom will endure the same killing duality, the Promethean endowment, hope and despair. The bible knows. The moment of human instrumentality, the apple, is the beginning of the Fall, not the Flight.

More than anybody I have lost, like the sound of the sea in a shell, Stanley’s voice is in my ear as I write. And it doesn’t sound sad. What a beauty he was. I get it. It isn’t great, this feeling, but what was I expecting? I’m seeking neither closure nor redemption. I’m not an imbecile. But, dear friend, I think I get it.

••••

It’s a beautiful piece you’ve written about your friend. Very moving. And I appreciate the unsentimentally of it.

Many thanks for sharing.

Both Sian, known also as Bogart, and his mother Sylvia, worked for us at Ornament Magazine, while we were located in Los Angeles, before we moved to the San Diego area in 1990. Sian also… Read more »

I’m pleased that this piece has rekindled old connections. Sian’s photography is not online anywhere, and it hurts to see somebody vanish.

I am an old friend of Sian. We have not been in touch for many years. I am shocked to learn that he has passed away. I have a number of his photographs that he… Read more »

Hey Kate. Nice to hear from you.Buzz me if you want to chat. I’m on IG (the Bellender).

Oh no. I just found this. I remember the house on Ripple and how far away and strange it seemed, on a hill and nothing around. Not even trees. Everything you wrote sounds and feels… Read more »

Hi Stephanie. Nice to hear from you. It would be cool if more of Sian’s stuff was available, but I don’t know how to get that to happen. Keep in touch.