Fever Dream. January in the Balkans

Tirana. Blind since birth, his irises white as milk, Andrea carries a folding stick with a ball on the end. He sits with it tucked along his forearm and unfolds it like a tent-pole when duty calls, or adventure. Click, click, click and he’s off. The driver assists him down the aisle, sits him beside me and we fill the hour to the city with chatter. He’s 27, studying in Bologna, architecture, but has never seen a building. He travels alone. We get off at Skanderberg, go arm-in-arm to his place, a backpacker’s hostel north of the river. Pride is not a factor, he says, if he’d listened to pride, even its whisper, he would never have left his bedroom. He functions through the kindness of strangers, and will stand and wait until it arrives; every arm through traffic, each bus and train, all currency, meals, rooms. And strangers never fail him. I tell him I’m sixty and he’s quiet for a few seconds then says, “I saw you as forty,” puzzled that his muse had momentarily misled him. After parting I slip through the city like a fish, uniquely aware of my prowess; to stop and start, swerve, speed up, slow down, the talent of vision, basking in the compliment of having seen and been seen, for once, without sight.

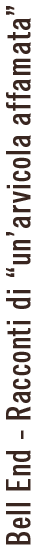

Bujar has owned Bar Bufe Basketi since 1991, when the regime fell. It has two tables, six seats and a counter, where he warms up stuff he cooked earlier at home. Soccer plays on a portable TV in the corner. He misunderstood ‘no meat’, heard ‘meat’ and brought me a plate of knobbly beef, the kind I’d have spat out at school, but I eat it here. One of the hazards of being nomadic; if you choose to engage, you have to eat what you are given. If you can’t chew it, swallow it. In the old days, he said (through his grandson Kujtim) they knew nothing of the world. Nothing. Nobody got out, nobody came in. It was horror out there, they were told, war and slavery and starvation. People struggled each day to put food in their mouths. Much better to be in here. Bujar means generous. Kujtim memory. If we suffered in here, he said, we still knew we lived in Paradise. His father had been to Ksamil, seen the lights of Corfu at sundown. “Proof,” they had said, “it is so terrible, they are forced even to work through the night.”

In 1992 Kujtim’s grandfather was given his first Coca-Cola. After drinking it, he kept the can on the mantelpiece as a souvenir. Shortly after, he saw – and ate – his first banana. Later that month, when Kujtim went to town, he asked his grandfather if he’d like him to bring back a banana. He said yes. When Kujtim returned with the banana, his grandfather thanked him but seemed disappointed. Later that evening he and Kujtim talked, and he admitted he’d been hoping for a red banana.

The bus terminal is a flyblown backwater from Graham Greene, shivering in the January sun. A dog wakes, barks, dashes off, returns, his morning’s work done. The buffet is Balkan Brief Encounter, its exasperated beehive proprietress pulling espresso, pushing chips. A couple kiss, Doisneau-style, in an open window above the only ashtray, already a volcano at 8 am. This is alive. One-way, long-way buses from one crap town to another, through the empty fields of industry, unpopulated lives, over streams the colour of antifreeze, to borders where we disembark, shuffle in groups, share fags. The man in the grocery shop at Bzhaj scampers off to find change for a 500, finds 200. I wave it off; I’m a few dusty meters from new horizons, a new story, where this currency becomes coloured paper. No use to me, some to him. But he insists. ‘Respect,’ he says. I take it, a buck-fifty, give it to a lady waiting with a kid. Love is amazing. Drugs too. Beyond that, this is good as it gets.

Podgorica. There’s no reason to end up in Podgorica. I thought I’d catch the train, the famous one from here to Belgrade, the only train, one train a day. But there’s nobody at the counter, in the station, nobody anywhere, not a sound, and the looming tunnel of eight hours waiting around seems bleak. It’s one of those moments. You can choose to go, you can choose not go. You can skip Sarajevo, skip Srebrenica, gallop straight to Romania, you might even make it to Gdansk and the boat across the Baltic. Or not. I find a room behind the bus station and wander into town past Caffe Balatazar which I snap a picture of to send to Keith, but he doesn’t respond. The center is a Lego-grid of nothing. Neither old nor new, sort of new-fashioned old, with cobbles and handicapped access. A town reimagined by post-conflict planners under the heading ‘town’. What it looked like before the most recent breed of Crusaders swaggered off, God only knows, so little evidence remains. There’s the obligatory wide-arched stone bridge. The vaguely Teutonic Town Hall. And now the sun has gone down, and as frequently happens, the best bet for food was the place you saw first, hours ago, back by the hotel. If it’s still open. You’ve squandered prime eating hours wandering like a hobo thinking you might find better.

Roštilj Janković lurks lonely, an Edward Hopper traveling salesman at the empty counter that runs from the bus station to the river. It does beer and meat, all kinds of meat, the animal kingdom burgled, mangled, stuffed into skins and incinerated. Only I’m not eating meat. Instead, Mr Janković brings me bread, wet cheese and a paprika and onion emulsion, from which I build tiny non-carnivorous towers, squashed with a palm; and clean my plate. I like this. I feel dainty and reverent, like a monk at compline in a charnel-house of sinning warthogs. Afterwards I walk the desolate train yards, watch the one train, the train I’d have been on, pull in like a wandering dog, cough, pull out. Its lights stay visible for minutes, slouching across the empty plain north, until the glittering millipede is swallowed up by the black mountains of Bosnia.

Srebrenica. We lost touch with Brendan’s drone outside the old battery factory. It dropped signal, befuddled by the echo chamber of vertical terrain. We’d just left DutchBat, where the UN soldiers were stationed in 1995, 370 of them, the designated safe zone where thirty-thousand Muslim refugees gathered on July 11th, and were planning a Srebenica flyover when the pulse on his iPhone vanished. We drove up and down the road, Brendan glued to his screen. There are not many people here now. Very few lights in windows as the sun goes down. All of a sudden he gets a beep. It’s in the woods above the road, so we set off in the minivan, leaving the others to kick around the cemetery with 8372 dead boys and men. We park next to a desolate apartment block under the skeptical eye of two women, one with a baby, and an old German Shepherd dogging its dirty days in the brambles. Brendan, desperate young Caledonian, scrambles up a steep face, clutching at branches and roots while I pant along behind calling out like a wounded lamb. “You see it? You see it?” After a while he calls back from far ahead. He’s found it, broken. The footage shows it was trying to come home, but hit a tree. Yeah, 8372 dead men and boys. There’s nothing left in Srebrenica. It is a town full of ghosts, just wants to be left alone to disappear. We pass the cemetery, field upon field of white obelisks, the soccer pitch, locked, and the battery factory once more, on the long road back to Sarajevo.

Belgrade. Marina plays the oboe in the Belgrade National Orchestra. We met for a moment in the lobby, me asking for wine, being given pear juice, and I must have peered down during Cenerentola, seen her chuckling in the woodwinds. The air in Tri šešira is blue with smoke, slavic voices clutter and shhh, all meat, mahogany and gingham. We could be anywhere. A snapshot would say Bucharest, Vienna, Sarajevo. She waves across the restaurant to a stranger, touches my hand as she rises. “Don’t go anywhere.” I feel the love go up my sleeve and come out of my hair. Everything behind you is behind you. The water you poured into the wine cannot be taken out. Alone on the 84 bus, crossing the Danube, you can make a fresh start with your next breath.

Have you forgotten what we were like then

when we were still first rate

and the day came fat with an apple in its mouth

it’s no use worrying about Time

but we did have a few tricks up our sleeves

and turned some sharp corners

the whole pasture looked like our meal

we didn’t need speedometers

we could manage cocktails out of ice and water

I wouldn’t want to be faster

or greener than now if you were with me O you

were the best of all my days

FO’H

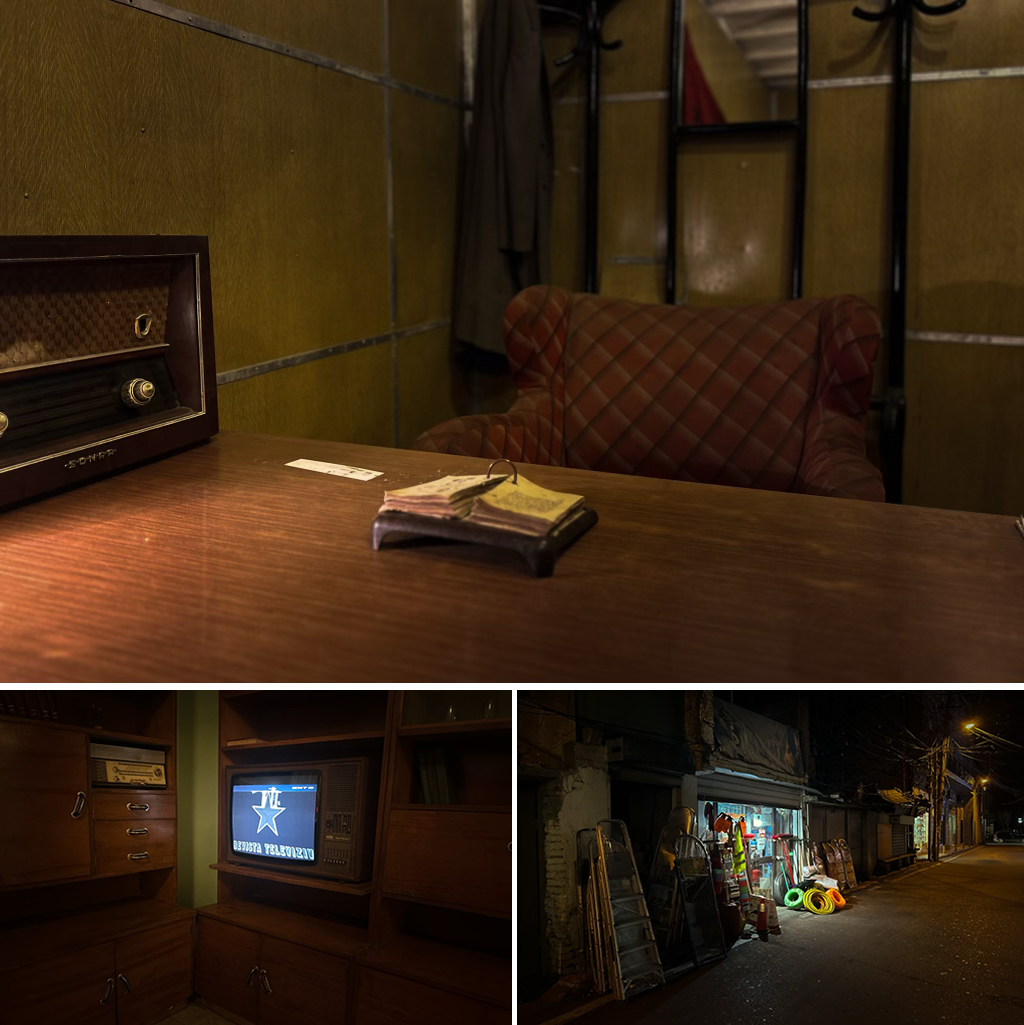

Timisoara. Timisoara is like Chekhov, its crumbling dachas and lace-curtained windows ooze melancholy so thick you could spread it with your thumbs. Like cheese. Like caviar. What ghosts can I summon from last time? Not much. I remember us cooking fish-fingers in a non-stick pan, but they weren’t fingers, they were fish. Fish-fish. The main square dug up like a field, its cobbles heaped against the buildings like cannonballs. The Romanian waitress in the Chinese restaurant down a long set of stairs, tending to us while a middle-aged Chinese woman looked on, suspicious. Unlikely customers, I suppose, in this subterranean palace of carp and dragons. So tall, she was, in her kimono, twice the height of her madam, her head scraping the ceiling like in some fever-dream Expressionist play. The three traveling salesmen choke on the bones of a pike before ever reaching the castle. I ask around but nobody knows the place. Timisoara, city of culture, has moved on. There are cappuccinos and mojitos now, and the Goethe-Institut is presenting The Cherry Orchard in German. I go, but the scenery collapses on the sprightly lesbian playing Yasha just as she is unleashing her signature hip-hop routine. The show is stopped and the police arrive. I am ushered from the lobby and upbraided after lingering for a photograph of the abandoned concession booth. There has been a tragedy. This is no time for art.

Elena, her youth ground down on Ceaușescu (whose wife shared her name) dines on soup and sarmale from the cafeteria. She’ll walk out later, bring it home in a box. What did Masha say about always wearing black? “I’m in mourning for my life.” Roaming the empty streets on the other side of the river, looking for the place we stayed five, six years ago, I slow down, watch her at the window. She’s motionless, a painting, other than the thin, looping skein of cigarette smoke. Winter days in the house upstate, foisted on the couch like a pupa, Juliette gone, the kids at school, icicles groaning like hanged men on the eaves, snow seamless to the low, unsurprising hills. Like death in slow-motion. I keep walking. Another two miles to the bus station.

••••