Take Me To The River Drop Me In The Water. Budapest

Slinking out of Athens with a hangover. I know nothing of Hungary. When we lived on Breuningstrasse, my dad would get bags of junk stamps which we’d toss in the bath, soak them slowly off scraps of old envelopes. I collected Magyar Posta, especially the Olympic Games ones, such drama, Socialist Realist discus throwers and hurdlers hurdling towards the future. How could things that looked so good be worth so little? Hungary. Might as well have been the Moon. We’d check their value in Gibbons, were stunned when one came in at 50p. Dad smoked Picadillys, lit one from the other, played the Vibrophone, the white Walt Dickerson of 28 Signal Regiment, mainly in Simon’s room because Simon was at school. They argued, my parents, all the couples in the block did. Some men threw their wives down stairs, locked them out in their underwear while they screamed like harpies and pounded on the doors. When it got rough I hid in my bedroom and when I was ill, delirious, I imagined a white space, a sheet, was being corrupted with black and I knew that I had to focus and keep some white because if it all got black it’d be over. We had Siamese fighting fish for a bit, until they ate each other.

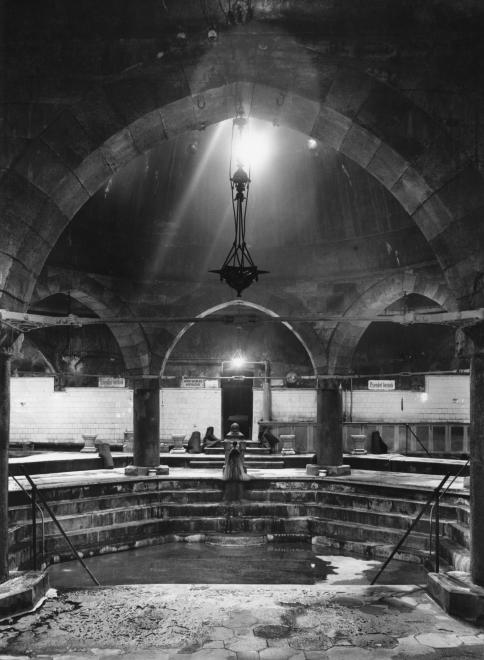

Rudas. I like how the men arrange themselves in the pools, their other manly stories democratized by little aprons, slung low and wet beneath each belly. Only vulnerable Tiresian buttocks, unplumped, tugged south by invisible fingers of gravity, speak to what joys and horrors have been suffered, behind them now, like old retainers. Here is Cicero, whose words command silence, drying on the parapet, holding forth to Nestor, an old stoat, they have heard him plenty. There will be a vote in the Senate tonight, can he count on them? Men whose clotted touch women endured, touch them no more, their slack probosces vestigial under scraps of linen. But there’s beauty in it; the pomp of impotence, comic now, echoed in dumbshow as the water hisses and laps. I am part of this and not part of it, the urge to be seen neutralized by nudity, short-sightedness and age. Auden’s words to his godson:

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

A poet’s hope: to be,

like some valley cheese,

local, but prized elsewhere.

Afterwards I take you up on your entreaty to call. It doesn’t come easy. It’s been years since the rugs of our lives overlapped, since we shared a winking purpose, cigarettes and easy dancing, your cappuccino body under that dress, bicycles and the ferry to Pellestrina. Your jawline sleeping, like Callas, always had other plans. And as we walk together through your house I feel nothing, other than a desire to get out. The cloying opulence, the awful old rats in the walls begging to be poisoned. And why do you keep saying ‘Aspen’? What was once lovely in you, the mongrel child, the girl smoking Marlboros who could speak every language, know every reference and still slug from the vodka bottle, has departed. Beauty like a tightened bow. Too tight. This winnowed reed, larded with wealth, is everything you had ached not to be. Gauche. Workers, hair matted with plaster-dust, nod to you like a contessa. The foreman pulls back wallpaper to reveal a lair of black mould, and you prickle, dismiss him with the hauteur of Nefertiti. I describe the tram ride from Astoria to the baths at Gellért and you stare back blankly like somebody who has never been on a tram.

Magyar Állami Operaház. Interval at the balcony bar. In another life they’d strike up a conversation. Never him though, never. The slightest glimpse of ‘creep’ in her eyes as he professorially moved the pages of the programme, ridiculous in Hungarian, would be a spear between the eyeballs.

Now Gorgythion, dead,

slumped his head sideways—like a garden poppy.

weighted down with seed and springtime showers of rain –

so drooped his head, weighed down by his heavy helmet.

But if he didn’t see it coming, maybe he’d manage. How do people wade into the storm drain of romance knowing they’ll wade out smelling like a pub toilet? The faint chance they won’t, he guessed; that scintilla of hope, whale-fat on the seams of corruption, keeping out the horizontal rain. For him destinations were always a little sad; some Ithaka of a morning bedroom, grizzled light and her wishing she hadn’t. A rejection of the journey, worse, a betrayal. What shone was that catch of light in crystal, the Giaconda smile, the acknowledged reciprocity that it wouldn’t happen, but it might have, another time, another dimension. The kindly, cosmic shrug, however glancing. The rest was an unbroken plain; the blur of Buda in rain from the tram window.

Horgásztanya Vendéglő. The soup is traditionally carp, which I remember from Witold Gombrowicz (who was Polish) but the waiter says they can do it with catfish ‘because the bones’. I wince, but plump for the carp, knowing the experience will be miserable and microscopic and I’ll be picking cartilage from my teeth for days.

“And fish milk?” he asks.

“That’s eggs?” I say.

“Sperm,” he replies.

“Y’mean like fish sperm?’

“Yes sir,’ he says reassuringly, like I thought it was maybe his sperm. Blimey. Fish jizz soup. I don’t remember that in Gombrowicz.

“You …” I do a wiggly gesture with my hand, “… the fish?”

He smiles.

“Is it disgusting?”

“It is like salt,” he says.

I pause for a moment.

“Okay, I’ll take it,” and he seems pleased, leans in so the next table can’t hear.

“We also eat the cock and the balls.”

Kaczián. Tiny, trim, with a flyover coif like Giulietta Simionato in Bacio di Tosca, the lady in Kaczián tie shop emerges from behind a curtain at the end of the counter. I see the Odeon flash of a three-bar fire, the nub of a croissant on a plate. It’s like I found an old lamp on the tram and rubbed it. Yes, she has cashmere; I can’t do silk, I say, it’s too toothy salesman. In the movie of me I am the Flaubert village schoolteacher, my satchel full of books, the country vet, wool tie tucked into shirt, sleeves rolled up, ready to deliver a midnight calf. Her shop reminds me of E Marinella in Napoli, I tell her, and she is momentarily puzzled until I show her the label in the tie I am wearing. “Oh,” she says, mimes a swoon, then shakes her head shyly as she slips my Black Watch cashmere into an envelope. “Il Maestro,” she says.

I saw Uncle Vanya in London in the 80’s. The bit when Vanya brings flowers to Yelena only to find her in the arms of Astrov was like a punch to the heart. Years traipsing to the theatre, I’d heard about these moments, read portentous reviews saying they happened every five minutes, but never experienced one. I had no money, was on the dole, but I went back two nights later, lay in wait for the explosion which once again caused an audible gulp throughout the auditorium. Michael Gambon’s strange little noise, the way this big man shuddered and crumbled before your eyes. I knew it could happen in life; I’d seen adults struck vacant by the death of a child, my brother. But in a play? Manufactured, alchemized? I thought theatre was people shouting at each other with ice-cream at the interval. But this was a Sistene moment, Sophoclean ‘never to have been born is best’ suspended at the tip of Adam’s finger. Like that line in a poem that lands when you’re not looking, sends you reeling about the room trying to comprehend what just happened. A finger through the membrane, a bead on the necklace of transcendence, a reason to press on.

Everything about those last years was like Chekhov. Sitting there, tending the samovar, days peeling off like scabs, cartwheeling them into infinity, wringing teardrops of interest from pointless husbandry, how many skinny bushels, must restock the wood pile before winter. Gazing out of the window, whining about ducks going to Moscow. And always somebody else’s luminous Yelena to my Vanya, sweating, grinning, clutching weak, propitiatory roses behind my back. It’s over now. We’re in the fifth act Chekhov didn’t write. 5 a.m. Gingerly, Vanya descends the ladder from his Airbnb loft bed in Budapest, crabwalks to the toilet for a piss.

In the forest outside Budapest, Karoly, out hunting truffles with his dogs, stumbles upon the naked body of a teenage girl. She is luminously beautiful, her skin radiating light, almost blue against the russets and burgundies of the undergrowth. She’s like that painting of drowned Ophelia, which he hadn’t seen, except in a book. A similar rapture, lips slightly parted, except this girl had no clothes on. He had never seen a woman so beautiful, certainly not naked, and he never would have, had he not seen this one now. “This is going to be a mess,” he thought, as he sat down beside her and began to skin an apple, feeding the peelings to his dogs.

I don’t know what the opera was. Wait, it was Butterfly, but we were were already shipping water by then, bailing while the boat went down. The bit where the little boy seeks her out, offers his hand for comfort, left us cold. We walked back over the Chain Bridge in silence, my mind scouring the surfaces for something to say, anything, another drink, breakfast tomorrow; but nothing. In the room, gaudy for romance, the double bed, I saw your shoulders sag as you looked around, imagining, hoping there was anywhere else. “It’s okay, I’m going back out,” I said, and threw my stuff into a bag while you were in the bathroom. This is how it happens. The light of wonder goes out while our backs are turned, we lose what we were allowed to be, all privileges revoked without recourse to protest. I took the tram to Kelenfold, sat in a coffee shop by the old station with the drunks and lost souls. You texted at 7; “where are you?” but I was half way to Vienna.

••••