West Union. Have You Built Your Ship of Death?

Flat on the floor in my underpants like I’ve had a seizure, there’s a string of drool sidling from my open mouth to a minor volcano of plaster dust three inches from my ear. I’m gazing at 18 inches of baseboard that needs painting, but I’d rather be suspended by lianas in the jungles of Madagascar with shards of bamboo growing up my ass than holding this brush. Mourning the heady days of April, when we gamboled between ladders like lambs, our woolly tails waggling with joy. Back then we’d prime and double-coat two ceilings a day, squawking along to the radio, cradling French 75’s. “Six short weeks and done!” we’d sing. Nine months on, we’re mired deeper than a grave, and it’s the Funeral March from Götterdämmerung, sepulchral groaning in catacombs under Naples where hollow-eyed skulls stare from faded frescoes of long-dead, once-jaunty noblemen. We don’t even pluck the pubes from cracks between the floorboards any more, just paint ‘em in. Booze underwrites everything, gurgling like the Styx; but now instead of fizzy with notes of citrus, it’s dark syrups of fernet and formaldehyde, alchemized to embalm. Why do we undertake to push huge knobbly balls of dung up hills without horizons on budgets so etiolated we must do everything despite knowing nothing? Whilst all along the street outside, real crews, wielding real tools and boxed lunches, smirk and cackle at the audacity of our folly. The electrician slows his truck, winds down the window to savour the aroma of vain hope, then drives on.

The toilet doesn’t flush. They say I ought to be grateful. We used not to have a toilet. Trouble is, the only thing worse than not having a toilet is having a toilet that doesn’t flush. Actually not flushing’s okay. You know where you stand; staring down at a toilet that doesn’t flush. You know what not to do. What sucks is replacing the shimmering air where a toilet once wasn’t with a toilet that now is, and might flush; but likely not. A toilet that flirts with flushing, winks and blushes, burps and sluices its furry cargo of bobbers halfway round the bend, only for them to slink back a few seconds later like bad bunnies in Mr McGregor’s garden. Only now the volume of water has tripled and our little Weetabixes have begun to disintegrate. Flush again and they’ll be gasping on the floor like stinky goldfish. Our new toilet is in the middle of the apartment, but we have no walls, so each evacuation is a public event, like the Pope’s Easter Homily or a coronation. All deposits (returned to sender) linger in the public domain until scooped up with a paint pot and tossed into the lobelias.

There’s a woman who visits me here when the Oryx is gone. Part tutor, part nurse, part meals-on-wheels, she instructs me in the art of being alone. Each time I lie in wait for the moment when I ought to turn away, when she sighs and knows she shouldn’t be here, but presses on with her ministrations. Maybe this visit will be her last. Something will click and I’ll get the hang of it. She leaves homework but I won’t do it. I can’t get my head around it, or maybe I just don’t want to. She’ll be back again tomorrow. I’m shit at this.

The Electrician, it turns out, is a figure from myth. Known in Germany as Der Blitzenmacher, he appears in the Icelandic Sagas as hooded Bjartframleiðand, glimpsed scuttling up the fjord at dawn, down at dusk, never once stopping. In Urdu he is Plug. When Dutch boys and girls wake from a long night breathing spores and solvents in the suburbs of Rotterdam, they rush from their bedroom squealing “Papi! Papi! Did Grootvader Schitter come? Did he? Did he?” Father shakes his head sadly. “Not this time, children,” he says, “but perhaps if we all pray at bedtime he will come tomorrow.” The family gazes wistfully at holes in walls and ceilings and the seething snakepit of extension cords that traverses the living room floor. Later, barefoot Liesl slips in a puddle of Father’s piss, the residue of him having missed the bowl in the middle of the night because there’s no fucking light in the cocksucking bathroom.

Not until the outlet pipe for the new washing machine goes in do you discover what happens when modern plumbing meets half a century of compacted human waste. Turns out the house’s juices have been barely escaping for decades, like thick ectoplasm, along sclerotic fecal arteries through stents of gerontic pubic hair. Plug in the new Whirlpool, cycle to heavy and stand back. “Thar she blows,” pipes Marcial, cradling a monkey wrench. A frothing geyser of flat-white erupts from the conduit, Jacobean tampons and mummified rodents dancing in the rainbows at its fringes. Residents of the Rondout flee wide-eyed toward the river, dogs twisting on leashes, soft-boiled eggs cooling on breakfast tables. Couples, effigied in embraces, are entombed through eternity by the deluge of effluential magma. Marcial snaps on elbow-length rubber gloves, uncoils a snake the girth of an anaconda and bids us retreat to higher ground, resume our decoupage and heavy drinking. When it’s over he emerges from the basement looking like he swam a mile through Willy Wonka’s. The Oryx smiles. “Is it okay to take a shower now?”

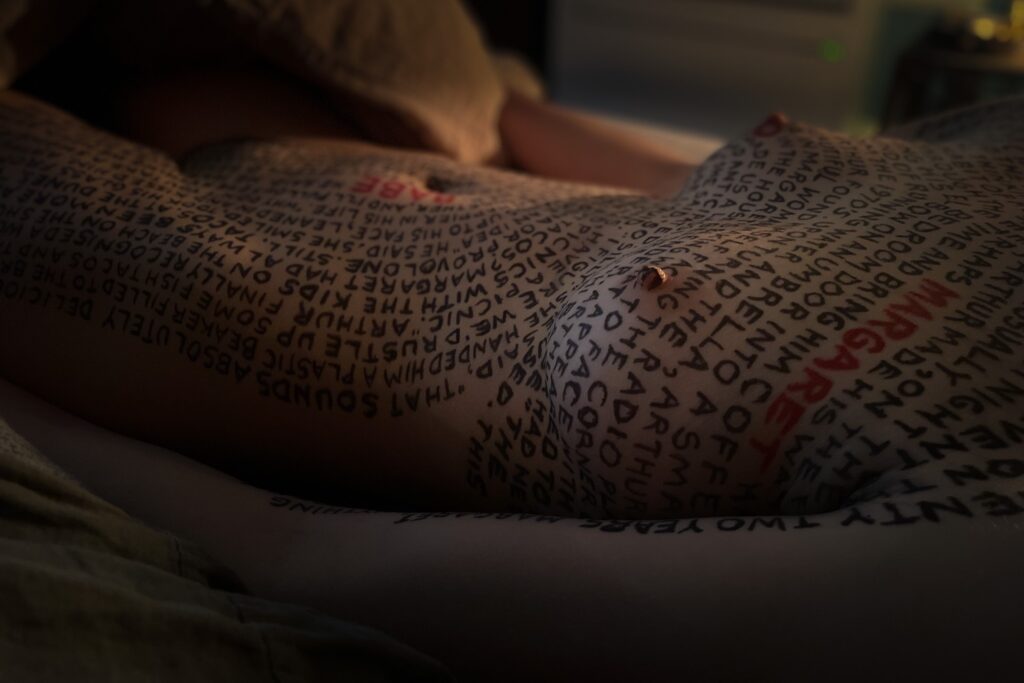

I lie in wait on the winding sheet as you go about your business. It’s a ritual that brooks no interruption, the purposeful back-and-forth between bathroom and dresser, emollients, balms, the vigorous opening and shutting of drawers, nimbly slipping off filigree day undies in favour of dowdy night ones. My head swivels, spectator at a slow-motion tennis match, but your silence, straight-line smile and lightly-cocked eyebrow confirm the performance is not for my benefit, would be the same without me, will be painless in spite of my dreams. The apogee – deft overhead removal of your t-shirt – is memory before it can catch fire and lay waste to the universe, as you turn and slip between the sheets in a practiced pas de bourrée. For a second or two I gaze at the ceiling, awaiting your decision. Then you curl, your softness against me, your warrior head on my chest.

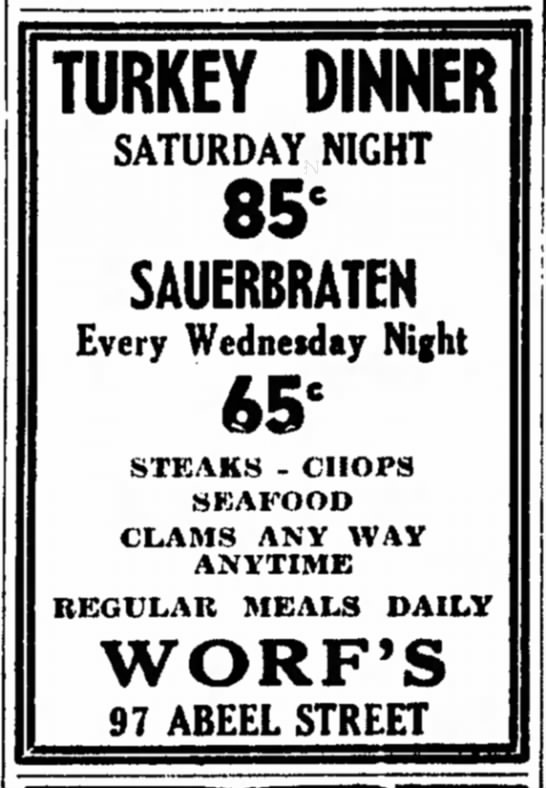

When establishing protocols for a happy and productive construction site, take care not to neglect the bar. Nobody should be ascending ladders holding a paint brush without also holding a white sbagliato. Orbital sanders barely function unless the arm gripping them is juiced with a beaker of Lillet. The Bruegel nightmare of Home Depot is rendered tolerable through the scarlet prism of a Spritz Campari, which also buffs the rough edges off shoplifting. The 6 am crowd at Stewart’s all become Ingrid Bergman with an eighth of Old Overholt in your hazelnut decaf. Operating a table saw without a Manhattan is verifiably hazardous; you could become dehydrated, bored, or even lose a finger. Hammers should swing to the rhythm of songs about Paddy shooting his dog, getting tossed out of a bar and throwing himself back through the window. Margarita hour is 4 on the button, attendance is mandatory and is followed by everybody barking like seals and firing the nail gun at each other.

One of the benefits of the crew living on site is early morning Dream Analysis over PG Tips before the hammers swing. Last night the Sheetrocker visited his cousin Heidi at a remote farm in Vermont. She’d just had a baby and when he got close to her she smelled of Campbell’s Soup. Well not the soup so much as the air inside the can after the soup’s gone and it’s sat around for a while, before you throw it away. Heidi mixed negronis and smoked Marlboro Lites whilst breast-feeding, cracked jokes about the zig-zags in her episiotomy. Nearby, a silent, boy-faced man hovered, grinning sheepishly. Heidi’s breasts moved darkly between the rooms and up window-panes, blotting out the sun. Twin dirigibles each with its distinct personality, they had greeted the Sheetrocker in the driveway as he pulled up. Heidi’s baby had a full set of teeth, like Matt Damon. It spoke in whole sentences, using words like ‘elderberry’ and ‘vicissitudes’. She asked the Sheetrocker to suckle one areola while Matt Damon masticated the other to meatloaf, ecstatically thrusting his etiolated hind limbs back and forth, then using them in tandem to push himself around the living room on his belly. As a consequence the child had extensive rug burns to one side of his face. On I90 just short of Albany, the Sheetrocker glanced in his rear-view mirror and saw the retreating, shouldered mass of his cousin’s bosom, still purple in the gloaming.

The bedroom looks like a burglary. It’s hard to leave the river-bank when the mercury’s in the 90’s and our little Wallmart boat, the Queen of the Rondout, beckons us with her plastic finger to abandon this blistered isle where we broil in the sun like pork butt. But if we’re not going to eschew clothes completely (neighbours recoil, blinded) we must house them. So we break out the Subaru, churn north past flyblown towns in unpeopled counties, to Fort Kitty and the Sharon Tavern on a crossroads to nowhere. Here we munch alone at the bar on Heather’s shrimp, our second great Heather of the week, the first being T-Mobile Heather and her TikTok pasta. I suddenly realise we’re in Schoharie County when Heather pronounces it like it’s frightening, which it is. So unexpectedly close to some frigid Catskills village impersonating an antique pie safe. We could pop in, say hi, grab books, brush up on pious isolation, make Mormon ice-cream from vanilla and a cold, cold uterus. Instead we lick the boot of Heather’s margarita, head east. Home before cocktail hour, dear, or the Subaru turns into a rutabaga.

On Sunday mornings we walk the dogged mile to Broadway Lights, the Oryx and me, for disco fries and bloody marys. It’s good; the cheese is whiz, not some nasty scab of mozzarella. I guess we’ve become regulars, an unlikely duo, wigged and frazzled from the chaste exertions of another Saturday evening home with the bottle. Mrs Chasin waves us to our booth by the window where, shoulder-to-shoulder, we fire up the crossword. Later she perches opposite. “You know what I miss most?” she says. Her friend in Macedonia died a week ago. She won’t go. She didn’t know the family. “I miss being there for her. You know, like a reason to go to sleep with the phone by the bed?” I get it. Beth. The lights go out while our backs are turned, getting groceries, arguing the electric bill. We lose what we were allowed to be, the privilege revoked, without recourse to protest. Meanwhile the expensive, delicate ship that must have seen something amazing, a girl falling out of the sky, has somewhere to go and sails calmly on.