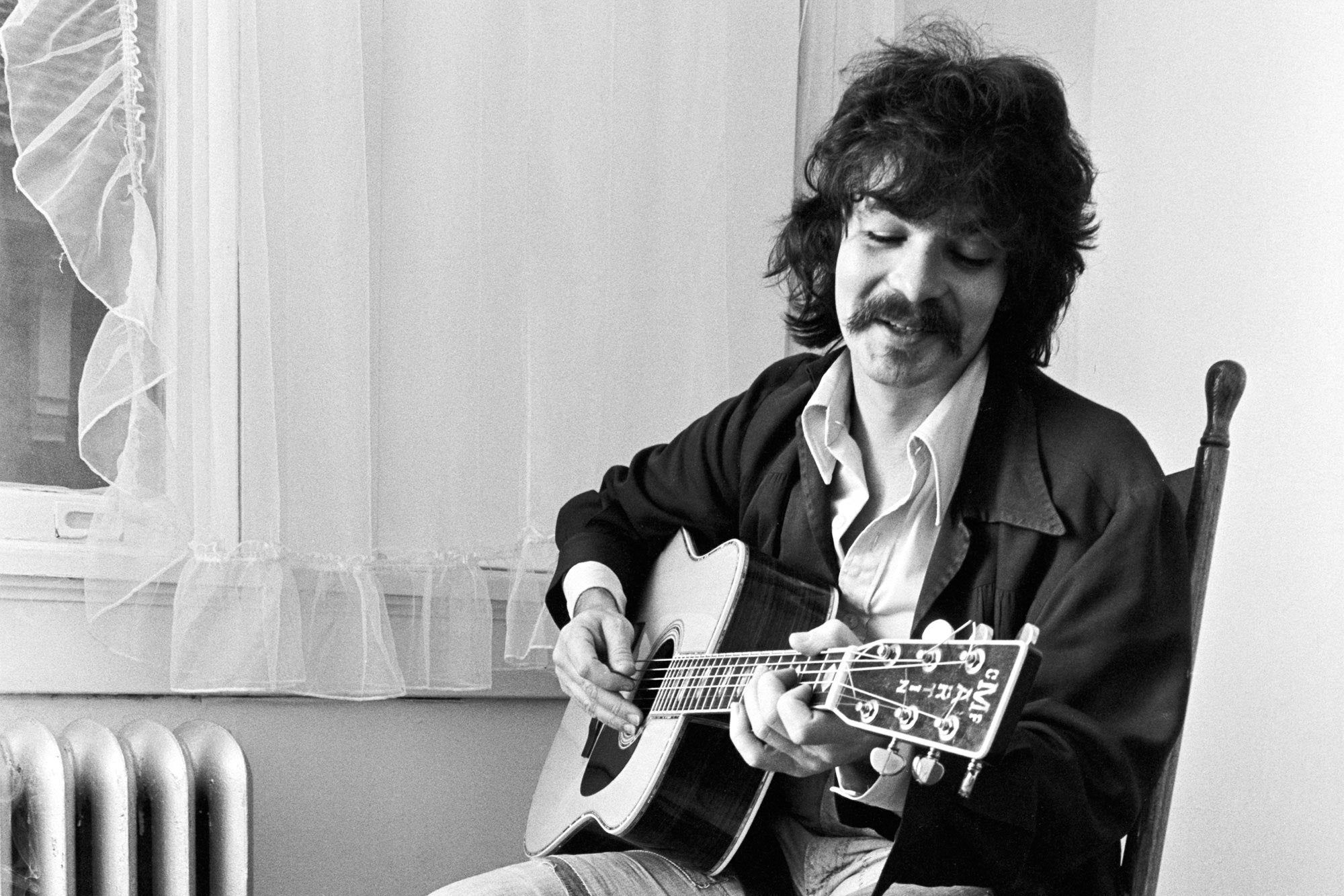

John Prine. Love in the Time of Plague

Some stuff is like an arrow, sprung exactly in time and space. There used to be a second-hand record shop next to the Army Recruiting Office in Oneonta, where Main Street tails off towards the Interstate. I remember sitting outside in the car on my own on a workaday upstate winter afternoon, and first hearing the words:

In an Appalachian Greyhound station

She sits there waiting, in a family way.

And just thinking; that’s here, right now. At the Trailways, round the back of the parking garage, that’s here. Like waking up with the echo of a voice still in your head. And the pregnant girl, with her brother in the waiting room, silent, because there’s nothing more to say. And after, later:

In a cold and gray town, a nurse says “Lay down,

This ain’t no playground. And this ain’t home.”

This ain’t home. And you just know it can’t be said better than that. When you’re inside a song, and your eyes well up and the hairs prickle on your neck because you know it’s real, and yeah, you’re in it, and it’s pure soul. Some guy with a guitar, three chords and the kindness to gift you the truth. Jack Gilbert said, ‘How strange and fine to get so near to it.’ And as we angle and simper, brand and lie, try to fake our way out of whatever ungodly mess we made, it is crushingly apposite we risk losing a voice like this. Confirmation of the desolation of providence. None of this cares for us. Ah baby. We gotta go now.

Shredded in the triangular piranha teeth of a break up, where your nerves are ribbons and your guts have been a clenched fist for as long as you can remember. Sitting alone on the bed in the damn homeschooling room, making a CD to say everything to her you couldn’t say yourself. Same shit, different medium, even since you were 12. Prine’s sad paean to unreasonable forgiveness:

But kids don’t know – they can only guess

How hard it is – to wish you happiness.

The way it rolls, quietly, like a mantra, like some guy – me – repeating the phrase in his head until maybe, one day, far in the future, he just might find the voice to say it:

I guess I wish – you all the best.

I played it over and over, as if I was in his skin, or he in mine. Then I’d go get in the truck and play it some more. All the way to the trailhead by the river in town, where I’d park, lie down on the bench seat, try to claw back some of the sleep the nights wouldn’t give. After a restless while, slope off to the guy with the hot dog cart by the side of route 10. Stocky, quiet, Vietnam Vet, he had a round face like a pie, an aw shucks smile and gentle, twinkling eyes. And a mailman moustache. John Prine face. I’d get two chili dogs and we’d shoot the breeze. Wry stories of tender defeat, stuff from years back, like sitting in the garage listening to the radio with the dogs. Then we’d walk to the embankment, toss potato rolls over the guardrail to the keening black fish in the river below. Never did find that voice.

Curled in the corner of the sofa as the news leaks and swirls. John Prine’s songs have been the punctuation of my life in America: three decades, two marriages, two children, the city, upstate. They coin the tracks of this murky road trip like a necklace. All the best bits. And the worst. So this news is too much to think about, too many flickering lights to put out at once. I’m listening to Lake Marie performed live somewhere: the plaintive camping trip, the flailing marriage, the sausages and shadows and dark lakes. And when he says, “ah, baby” and you feel that rush of blood, the tingle in your fingers, when everybody understands what two words mean. Like a shaft of light through a ladder in the chair-hung stocking. Back then I ached for England and how clever and witty we were, how we strutted and preened and scoffed and squawked. And everything we did. But we didn’t do that. Such soul, wit, kindness, love, decency, beauty. And it made America seem great, seem worth it.

••••