Asia Minor. West To Constantinople

The man behind the glass presents my ticket like it’s the Legion of Honour; an embossed diploma in red, blue and gold, twenty-two grand for a hundred-and-sixty-eight miles, eleven hours and a bunk with a dude from Grozny. Yerevan to Tbilisi. Thirty-eight bucks. He smiles wistfully. “Not Orient Express,” he says. In the litter of bus stops behind the station men play chess at plastic tables, spike peach iced-tea with vodka. One stands. “Boyfriend,” he says, then gestures to me and to skewers of meat. “Yes?” Yes. Yes to lamb. Yes to lavash. Just yes. A man advances at a crouch waving a chicken leg and shouting. He has an idea. He’s looking for someone and when he finds them they’ll get a piece of his poultry. A dog slithers out from under a bus. The man squats, gives the dog the chicken, they exchange pleasantries, he boards the bus. “Barekamutyun!” he shouts, and fires up the engine.

On the train approaching Gyumri they bring us coffee and cookies. I doze and wake to find the knot in Yerevan’s shoulders has eased; the princess has outslept the pea. How casually joy wilts, like it stopped paying attention, becomes desiccated seemingly by the hour. The leaves of some insipid tea, fines herbes, on a tray in a old lady’s window. We prattle and cluck, bury the knowledge that we were probably wrong about the way things used to be, recalling them through a drizzle of nostalgia fortified by snobbery. We say we were happier then, our only regret being we didn’t know at the time. Only later do we come to realize we were never as happy as our recollection insists. Neither ourselves nor those we touched. They told us, but we refused to listen. Meanwhile I trundle towards Tbilisi, relieved once again to be the smug casualty of my own idiotic miscues. My cabin companion, a Russian wrestler bound for Batumi, plies me with sweet bread and cold-brew cappuccino in plastic pots, no matter how winsomely I wave him off. This morning she wrote again, more unearthed memories, reminding me about the book I sent her for her wedding; the first edition of poems, my inscription curled beneath the flyleaf like an adder. She should have glanced once and given it straight back. Instead it landed on her wall somewhere, venom dripping from shelf to shelf. She said she’d used it to remind herself (as if she ever doubted) how convinced I was of my right to strike. Defanged, I watch families slumped in their cars under the hammer heat of the station parking lot, their doors open, waiting as the train pulls in.

Before he had a chance to register it, the thing that had been happening was over. He turned to take the dinner out of the oven and when he turned back she was gone. Just her seat, pushed slightly back, still at the table. For a while afterward her voice would wake him in the night, like she was in the room, or closer, her head next to his on the pillow. Then slowly it faded. He tried to talk to her, to talk out loud, but there was nobody there. Or if there was he couldn’t hear them. Everything stopped. She just went away. Now he rides trains, sleeps on ships, and still he hears her voice. Today he heard it next to the petrol station in Malatia. It’s like every woman has her voice.

The woman in the box next to me is a character from Tolstoy. Slight-waisted, summer dress, french braid, I see her from the side, drumming her fingers lightly to the music. At the interval we acknowledge each other; dark, Georgian, and she smiles. During the next act she dandles a child, a boy, her Seryozha I imagine, on her lap. This slice of life I have extracted has been rich with loveliness. Would a different slice have been different? I doubt it. There are lovely people everywhere. You just have to be up for it.

Tbilisi Central Station, supine colossus, barren Soviet matriarch; I’m lurking in the womb of this concrete dinosaur waiting for the train, the only train, the train I’ll be on. Turns out I love this town. It’s a crush. I saw it out of the corner of my eye, it smiled and I was hooked. I can’t quite grasp the syntax of the feeling; it’s slippery, a twisting cotton thread, unworked. I felt it in the fleshpots of the bus station, in the packed marshrutka with Charlotte, swerving north to Mtskheta, and when Dani brought me trout dumplings. I don’t really know what love is, but I know when it’s around. Hold hands, uncross your legs; the spirit is upon us.

He woke up transported by love. The first person he ever worshipped was a boy. Made sense, really, sequestered at a school full of boys. A lot of forks and knives. Gotta cut somethin’. It wasn’t physical back then, little more than feverishly holding hands after lights out. But in the dream the boy sidled into his study, smirking, wanting something, a Rich Tea biscuit perhaps, and he said “don’t you flirt with me,” and the boy walked over and kissed hm. In truth he’d never have said that; and the boy would never have done it. But no kiss has ever been better. He’s never wanted to be with a man, but he’d be with this boy. It would be everything. Sex, he believes, is the manifestation of love, or ought to be. That way the taxonomy, the vaunted nuts and bolts, seem not to matter. Or so his dream said.

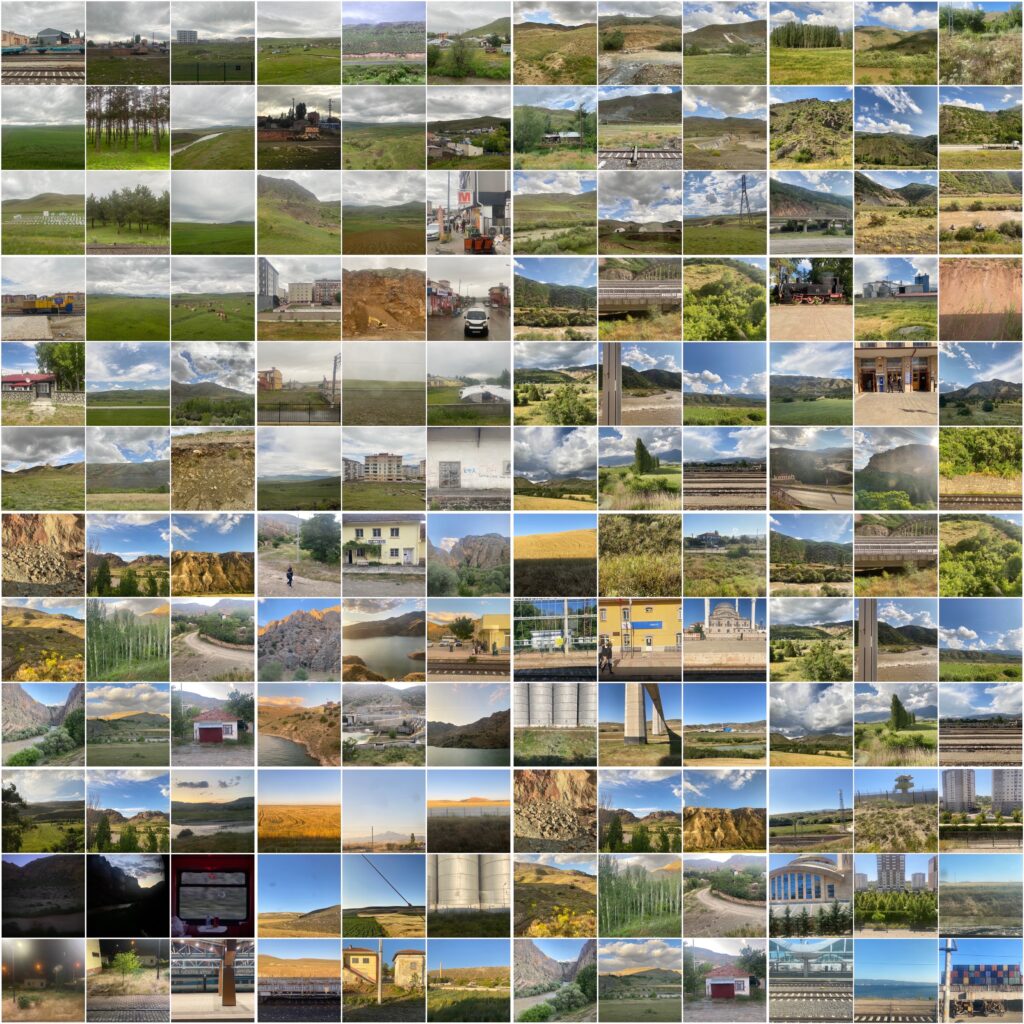

By the bus stop in Hopa a man with thick glasses brings me breakfast; four meatballs in a bowl of broth, a plate of cucumbers and tomatoes, tea. He’s wearing a tie and red hat, same as his colleagues, three of them. I found an innocent hour stepping across the Anatolian border, so it’s only 7.30 and I’m the first customer of the day. I take a few sips of tea, sit back, look around and savour the rising wave you get in your chest when you feel like you’ve nailed it. A light blanket of harmony. The way it sluices up from nowhere, like ectoplasm. Perfect. Nobody cares for this. Everybody’s looking for something. Towns heap up on the horizon, people are falling over each other, flipping the cushions, tearing down the scenery to find whatever it is, the same thing as everybody else. Nobody’s looking for nothing. Selda told me Kars is the city God forgot. Hanin concurred. It sounded like vilification, but it isn’t. Because nothing, they know, is so much better than something.

“There is no solace in dust,” he said. “We begin in dust and end in it, and the time between is rumination on dust.” What gift is this, this talent to contemplate our own futility? I nodded, gazing out to where he gazed, the heroic sunset, the lights of Gelibolu, necklace at the bare throat of the Sea of Marmara. He gestured towards the beauty as if to wave it off. “Seems like something, but it is nothing, no more to us than to a crab. But oh, this voice that tells us it cannot be. Gift? No, this is an affliction.” I thought of the Cranachs in Brussels, the pluck of the apple, a shimmering bolt of consciousness then forever cursed. We were quiet as the shoulder of land sloped away into the desert of the Mediterranean, sipped the raki he had rhapsodized, basked in the unconscionable pettiness of being alive.

Alone at the cafe with the book he wasn’t reading, another town, another knot in the thread, already they knew him. The Englishman strung out on a woman, better without her (everyone said) which is exactly what he was; yet sick to the stomach, seeing every inch of the world through her eyes. That night they had argued in the room above Santo Spirito, pulled the beds apart. He left, walked the streets till dawn, hoping for what? She’d miss him? Wake up contrite, wishing he was beside her? All he wanted was to be pocketed in the corporeal fog of her approval. How many hours murdered in desolation before pride led him back up the stairs to turn the handle and find her contentedly asleep. “How long were you out?“ she said in the morning, emerging from the bathroom dressed for breakfast. And now, another town, same ache, different face. He’d come a long way to feel this keenly low. Torn off bits of bread and left no trail. That night he’d sit at the table, sip grappa, as if the image, painstakingly crafted, could cross oceans, enter her dreams and, with the terrible force of his love, change her mind.

The steps of Quartieri Spagnoli run orange with Aperol. Palermo is pedestrianized eat-on-the-street. Prague fell years ago, Budapest, Krakow. English policemen stalk stag nights in Ljubljana, Bratislava. Here in Kadiköy it’s all-night Tuborg at the Bristol Pub, the Tarantula Bar weeps raki, techno thumps in Harlem Jazz & Blues. In Moda the call to prayer soars like a kestrel over Taylor Swift grinding her filly thighs like a mangle. So this is what freedom looks like. A seagull sucks down chips and a doner. Coming in low over the Sea of Marmara, sweet Exocet, silent silver cigar, above the lights of Heybeliada, Burgazada, Kinaliada, banks, and with a whoosh plunges into the sheer blue mirror of the Doubletree, soft as a stiletto. A beat, a clap of thunder, a ball of flame. I wipe köfte from my chin. I’m drooling.

•••