Grandi Navi Veloci. Slow Boat to Tunis

Alone in my cabin but for a half bottle of Tunisian red and a cheese toastie, porthole squinting like a sunbather onto a blaze of yellow North African light over seamless aquamarine. The ship’s all Arabs; the last Europeans – nervous ladies with dogs – were deposited in Palermo this morning. On the upper deck brown men slouch at tables around the empty, netted pool, the shied core of a once crisp maritime apple, tossed towards the bucket of the leisure classes, missed by a mile. Sweep it into a corner with the shuttered casino and piano bar, the variety stage given over to a committee of immigration officers, demanding, rejecting and ultimately stamping sheaves of documents, surly as the Taliban. Supine on my bunk, shuddered by the engine’s articulated throb, I’m tweezering the final fragments of a two-year game of Operation, sea-borne monocled microsurgery. We’ve arrived at Wretched Ankle; Funny Bone’s in the bag (wasn’t all that funny), Broken Heart so long ago I’ve forgotten. Despite frequent alarms, the patient is dead. Retweaking Wishbone, a verse from a poem I liked as a teenager ghosts out of the Tyrrhenian like the white whale. Seems cells were dividing, even back then, that would eventually coalesce into organs of understanding. And it’s an odd rush, time compressed over decades, distant points suddenly cheek-by-jowl, like some quantum accordion, where things far apart are actually very close. The now me, hand on the shoulder of the then me, like it always was. Takes half a life to understand four lines.

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

‘I am moved by fancies that are curled

Around these images, and cling:

The notion of some infinitely gentle

Infinitely suffering thing.’

We were in a tiny casino in Puerto Natales when we heard that Hugh had died. I saw it over the dealer’s shoulder, the only dealer at the only table, and us the only guests. A newsreader, Hugh’s face on the screen, ‘Muerto a los 58,’ then people protesting near a dam. Chris had gone to the toilet. “Hugh’s dead,” I said when he came back. We finished our drinks, pisco sours, bought a bottle of wine, walked in sempiternal twilight past the above-ground cemetery – Patagonian bodies hovering endlessly above the permafrost – under strange-eyed constellations to our hostel, where I lay on my bunk and gazed up at a sheet of plywood; whilst Hugh, sightless and half a world away, did the same. I could almost hear him not breathing. Never breathing again. On the portion of that unknown plain we’ll both for ever be.

The ship slouches into port four hours late. Midnight, no sign of a city, just floodlit fields of docks, and beyond, hulking shadows of sandy hills. We disembark along a gangplank into a featureless hall, weary hundreds descending upon a single immigration hut containing a single immigration officer. He listens to each plea with the skepticism of a small-town magistrate. It wasn’t your brother’s goat? You didn’t slap your wife? Each encounter is cause for remonstration, the spectre of denial, three days on the ship back to Genoa, doggy tail between doggy legs. Yet nobody is denied; each plaintiff is lectured, grunted at, then stamped through with an air of disgust. And me? “Address!?” I show an Airbnb listing on my phone. Chic 113 Year Old Apartment in the Heart of Old Tunis. I might as well be promulgating my nephew’s bar-mitzvah. “Hotel!?” he barks. “Airbnb.” I say. The crowd gazes over my shoulder, coo and murmur as I scroll through full kitchen with stove and coffee-pot, and charming balcony view of Habib Bourguiba and the Porte de France. “Hotel!?” again. A man behind me pleads for me in Arabic. “Just let the old man through, inshallah, we all want to go home.” He is dismissed with a wave of a hand. Piqued, he begins shouting, gesticulating towards the heavens, is joined by another man and another and several women. People are ululating. It’s beginning to feel like a Palestinian funeral. The immigration official barks a command or a curse, stamps my passport. I am in.

There is no city. There are no taxis. There is a roundabout. A thin man approaches. ‘Stay here,’ he says with his hands, and scampers off, returning with a folding chair and a small bottle of water. ‘Sit’. I do. He vanishes. I’m tired, but safe. If I stay here and wait something will happen. The air is warm and smells of flowers. I won’t rot away or be eaten by dogs. I don’t speak Arabic, I don’t speak French, other than set off on foot what more can I do? A fat man crosses the road, points to my chair. I point to the spot where the thin man had found it. The fat man points at his chest. I stand up, he takes the chair to where it had come from and sits. A car drives up. The thin man gets out. The fat man points at him. “Is this the thieving monkey who stole my chair?” I shrug. He raises his hands to Allah. They both laugh.

The woman opposite sits in a wheelchair day and night. Other than a small table, there is no furniture in her room, which is towering, Italianate, the walls empty, decomposing. Plaster has fallen from the ceiling, exposing broad sheets of lath. There is no glass in the french windows. A swathe of fabric, hung long ago from the iron railing, bleached and crusted into crenellations, recalls the Michelangelo Pieta. A single lightbulb hangs from an extension cord which traverses the room at head height. It is on day and night. Today a small school chair appeared on the balcony, facing in. She had a visitor. A man in a long shirt and sirwal pants. Now he is gone. The end of the affair. It’s like the cat on our street with the broken jaw. Yesterday she had babies. Now she has none.

High above the waste and rubble, the spectral tide of skeletal cats, the torn black garbage bag of false teeth and dental impressions, the tragedy for the limerick composer is that Tunis doesn’t rhyme with penis. If it did, anything might be possible. The round old man with one bottom tooth, a character actor from Camus, browbeaten, disappointed, stops us on the tram platform to practice his English. He says the city is vulgar, brutal, makes a face of pure disgust. He lived in Amsterdam, a beautiful city, but came back when his father became ill. You cannot abandon your father. And now he is stuck here, will die here. Everybody hates it, he says, only the Belgians like it because they are stupid. We ask if he is a philosopher. “It’s philosophy you want?’ he says, then points to a beer bar, a den of sin, two men guarding the door and a fog of smoke. “It’s all philosophy in there.”

Existentially French Jean-Paul Sartre,

Could do wonderful things with a fartre,

“If you pardon the smellin’

I’ll mimic the bell in

The gothic cathedral at Chartres.”

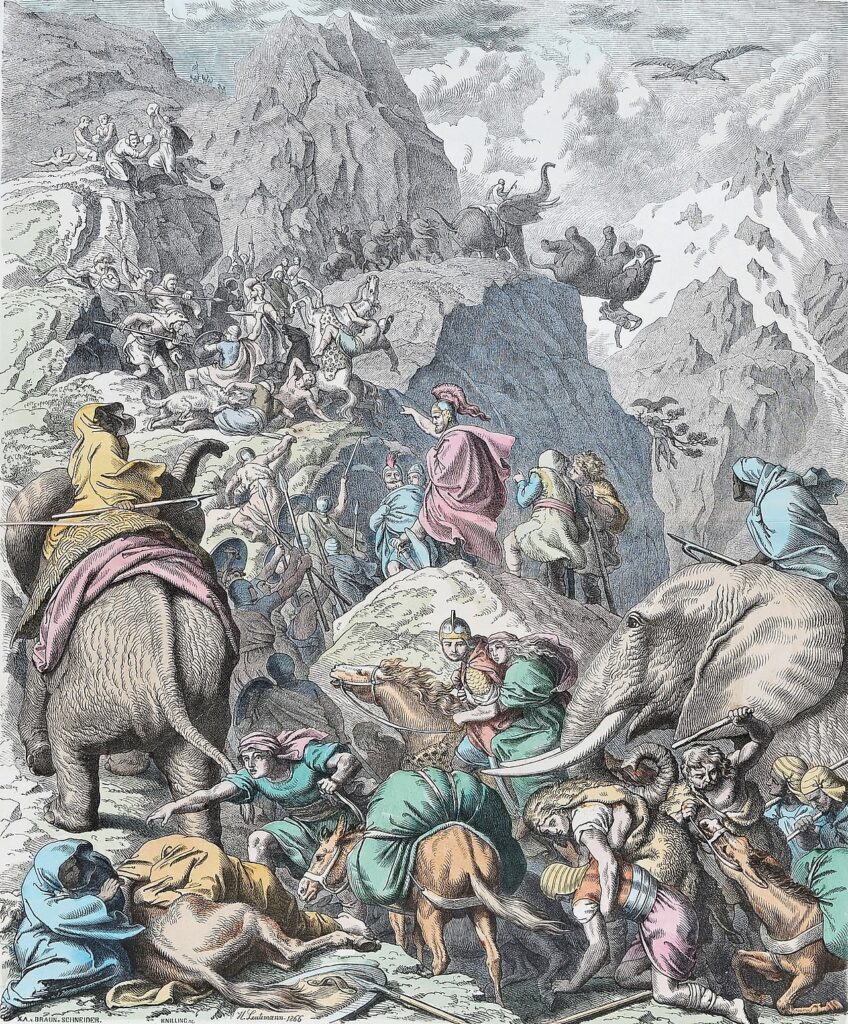

Muhammad Ali ate here. He is there on the wall, a faded shoutout to Monsieur Hassouna Arfaoui scrawled across his chest. Here is Edith Piaf. Michael York, Simone Signoret, Jacques Chirac. Scanning the menu, a series of apologetic “non’s” afford us only what remains; poulet à la milanaise and puttanesca with tuna. The people of Tunis eat a lot of tuna. A misunderstood word? A misdirected freighter? “Take all this to the place on the can.” There are shoals of it on shelves of otherwise half-empty supermarkets. Two men in guayaberas and Panama hats, extras from Buena Vista Social Club, linger in the corner. They are not eating. We will be Chez Nous’ only customers tonight. One man rises, sidles over, keen to hold forth on the historical intricacies of Tunisian-American relations. Tunisia was the first nation to recognize the newly independent United States, he says, “la première!” and makes strident gestures with his arms, his upper-lip taut, like a beak, behind a David Niven moustache. “Plus de gentillesse,” is all he expects, not necessarily from us, but from Lady Liberty, who appears to have forgotten her starving old friend. We grin sheepishly. “Pas Américains,” we mumble. The African waiter, Mister Ladu, a Dinka from South Sudan, blue-black as ink, slips plates in front of us. Chicken nuggets and a can of tuna over spaghetti. Our new friend moves on to Hannibal, Tunisian, great General of Carthage, led elephants over Alps, punched the Romans on their noses. He punches. We understand? We understand. It’s Friday, Ju’muah, so the city is dry, the dog-eared litter of man-bars closed. No Tunisian wine with our tuna. On my way to the bathroom, I pass the kitchen and Mister Ladu washing our dishes. “Aussi le chef,” he says with quiet modesty. He dries his hands, beckons me to a door beside the ladies toilet, which opens onto a corridor, another corridor, some stairs. Music swells as we move deeper into the building, American hip-hop, pounding. Finally another door, the music bursting forth as we emerge into a symphony of wine glasses, cigarette smoke, men and women of all ages, chattering, drinking, dancing. There are men with dreadlocks, women in tank tops, long hair, bare skin, laughter. We could be in Belleville, Shoreditch, Williamsburg. Or Casablanca. Peter Lorre sits at a table with Sydney Greenstreet, Humphrey Bogart smiles at Ingrid Bergman. In the end, inshallah, a kiss is just a kiss.

Upon returning from North Africa, Kenneth Halliwell beat Joe Orton to death with a claw-hammer in their Islington bedsit, the wall-to-wall decoupage newly embroidered with brain matter. Not that there was a connection necessarily, but there’s something visceral, vainglorious in his gesture that smells of Arabia. Between-the-wars colonial élan, a cocked fez and the twirl of a swagger-stick. Twenty hours out of Tunis I glance over at Paul in his bunk, all pink and Y-fronted, glued to his Iris Murdoch, and think what a story it would make. Murder on the Ligurian; a sanguine explosion off Livorno where Shelley drowned, straight out of Patricia Highsmith. Except I don’t have a hammer. Only an electric toothbrush. Still, if social media proves anything, it’s the unholy power of earnest mediocrity.

•••