Abeel Street. The Dutch Are Coming

‘As beautiful a land as one can tread upon’

It’s the summer of ’09. 1609. Having twice attempted, twice failed, to navigate an ice-free passage past the North Pole to Asia, Henry Hudson and the crew of the Halve Maen find themselves labouring up the east coast of America, beset by storms and gazing once more into the maw of humiliating defeat. The patience of his Dutch sponsors long exhausted, Henry is faced with the choice of limping home with his explorer’s tail between his legs, or fashioning redemption through pulling a pioneering rabbit out of a hat. Ever the opportunist, he plumps for the latter, steering into an estuary previously observed by Florentine navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano, and setting sail up the mighty river that would later bear his name. ‘The Northwest Passage!’ he cheers. His crew stare back at him like Easter Island statues.

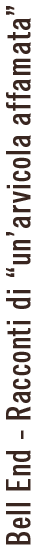

Ninety miles upstream it’s not looking good. The Pacific Ocean feels a long way off and it’s becoming clear that whatever passage this might be, it isn’t the one that will unlock the storied riches of the Orient. The scenery’s nice and the natives cheerful, but the river’s getting smaller and there’s no sign of sampans. Where the sweet waters of Groote Esopus run into the tidal Mauritius, Hudson pauses; his crew fish ‘a great store of very good salmons’ and meet ‘a very loving people, and very old men’. Rondout. They’ve reached Rondout. Or what Rondout would be if it only knew what was coming.

Catelyn Trico, arriving on the Dutch West India Company’s New Netherland fifteen years later, found a place where ‘the savages have much maize-land, but all somewhat stony.’ Had she hung about a couple more decades, she might have raised a flagon with Captain Christofell ‘Kit’ Davits in celebration of having sold brandy to a group of Indians who, inebriated, went on to massacre his mother-in-law.

‘Aert Jacobsz, who had the neighboring farm, also ran a tavern. In 1646 Gerrit van Wescom went there to buy brandy and was assaulted by a drunken Indian, who would have strangled him had not another Indian intervened. The next year another neighbor, Ryck Rutgers, was involved in a general melee. Kit Davits hit Ryck in the head with a post, then hit Jan van Bremen in the head with a beer stein, and beat another man black and blue, while Jacob Flodder was busy using a beer stein on the head of Poulus the Norwegian.’

By the time Peter Stuyvesant arrived in 1658, his wooden leg studded with silver nails, Esoopes was Wiltwyck. Wild Place. The confluence of Esopus, Rondout and Wallkill creeks has been a storied crook at the elbow of the Hudson for more than four hundred years. Revolutionary spirit swirls in its eddies. In February 1777, the New York Congress of Patriots, escaping the noose drawn around Manhattan by British forces, evacuated to Fishkill with the intention of inaugurating the first Independent Congress. Sadly for Fishkill, there was nowhere nice to stay, so they decamped to Kingston, pronouncing it the first Capital of New York. The British responded by burning ‘this hotbed of perfidy and sedulous disloyalty’ to the ground. They came from the river, their boats anchored at the mouth of the Rondout. From our position on Abeel Street we could have watched the Redcoats ascend the hill and been among the first to feel the smart of their torches as they set about pillaging what Lieutenant-General Sir John Vaughan had declared to be ‘a nursery for almost every villain in the Country’.

John Vanderlyn, father of the Hudson River School, born in Kingston in 1775, painted landscapes from the heights above Rondout whilst scandalizing the nation with Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos, the first nude painting exhibited in America. On the back of this notoriety, he opened the nation’s first private gallery, the Rotunda, showcasing his patented 360º panoramas and portraits of Presidents. It bankrupted him. He fled to Paris before returning to Kingston where he died in 1852, penniless and alone, in a cheap hotel. The Rondout has always courted art, degeneracy and hospitality, often seamlessly. We inherit a rich tradition.

Rondout’s story flourishes in 1825, with Maurice and John Wurts’ newly-minted dream of transporting coal from rural Pennsylvania to New York City. The Delaware & Hudson Canal. 108 miles of locks, aqueducts and reservoirs stretching from Honesville to Rondout. In the space of a year, our erstwhile backwater was transformed into a seething shanty-town of immigrant laborers, furthering the American Industrial Revolution with pick, spade and vast quantities of booze. By 1828 there were fifty saloons and a blinding number of underground speakeasy’s scattered across Vanderlyn’s Arcadia. The Corkonians fought each other, their wives and the Germans. The Germans fought the Blacks. Everyone fought the Bumble Bee Boys. Riots, beatings and stabbings were commonplace. The Rondout Courier noted that on April 7th a drunken virago entered Canfield’s Tin Shop in search of her husband and, upon finding him absent, cursed the multitude at great volume before smashing the shop windows with her fists. It was pure Gangs of New York:

Ramshackle housing replaced field and orchard, buildings seemingly dropped from the sky ‘stuck fast wherever they struck’. The air was thick with ‘sickening stenches and rankness overpowering’. Sewage was routinely dumped out of windows, pigs ran unchecked through the streets. Not even the Dead were safe. The Courier, on December 8th, urged citizens to curb their swine’s peregrinations in the cemetery and thus ‘prevent the graves and their inhabitants from being washed and rooted down the hill.’

This was the ‘nest of hornets stirred up with a crooked stick’ into which Abeel Street – named after D&H Canal director Garret Abeel – was born. Nestled between the First Presbyterian Church, St. Mary’s, St Peter’s, the First Baptists, Shanghai Bob’s Turkey Buzzard Saloon, Congregation Ahavath Israel, the Episcopal Church of the Holy Spirit, St Mark’s African, Jacob Forst’s Chicago Dressed Beef, the Trinity Evangelical Lutherans, The Radical Perfectionists and the Dutch Church of the Comforter … 101 Abeel was constructed to house Irish laborers upstairs, mules down. It was the heyday of the Canal Age, and Rondout was its apex.

But in the maelstrom of Industrial Capitalism, nothing lasts forever. A flood in 1888 inundated the D&H, demolishing the locks at Eddyville. It was a harbinger of things to come. The first railroad lines from the city had been established by Thomas Cornell as early as 1870. The Rondout & Oswego Railroad seamlessly connected Hudson River steamboats – at the spectacular, newly-developed, Kingston Point Park – to the luxury Mountain Houses that had sprung up across the Catskills: the Overlook, the Grand, the Kaaterskill. It was only a matter of time before this more efficient form of transport also came to dominate the movement of freight. 1n 1898, the D&H Canal, well-spring of Rondout’s prosperity, was closed. Built 73 years earlier at a cost of $1.4 million, it was sold to the only bidder, Samuel Coykendall, for $10,000. Whilst the great steamboats – Washington Irving, Chauncey M. Depew and Mary Powell – continued to ferry thousands of tourists from New York to the railroads and on into the Catskill Mountains, Rondout’s golden years were coming to an end.

By the time the Mary Powell was decommissioned in 1917, the city’s maritime traditions were in terminal decline. Without its connection to the river, Rondout’s heart was effectively broken. The image of the great steamboat, emblem of Rondout’s pride and prosperity, beached like a whale across the creek being dismantled and sold for scrap, became an enduring metaphor for the city itself.

•••